The Public Lab Blog

stories from the Public Lab community

About the blog | Research | Methods

Net Neutrality: resources for action

Image obtained from: https://imgur.com/gallery/zfxwB

Hi Folks,

The FCC will likely be voting to repeal Net Neutrality on December 14th. The two main modes of civic engagement to protect Net Neutrality are to (1) contact Congress (who oversees the FCC) to remove or delay the scheduled vote, and (2) contact the FCC and tell them to NOT repeal Net Neutrality. There are also protests scheduled outside of Verizon stores (since the head of the FCC used to be a top lawyer for Verizon).

Some resources for civic engagement are:

Contact Congress: http://act.freepress.net/call/internet_nn_call_congress/

Contact FCC: http://act.freepress.net/sign/internet_wake_up_destroy

Find a local protest: https://www.battleforthenet.com/

There are some great informational resources available about what Net Neutrality is, why it is important, the regulatory context of it, and political and social analyses of the current proposal:

For clear and concise information about Net Neutrality and its importance, please see: https://www.savetheinternet.com/net-neutrality-what-you-need-know-now

For more discussion of its importance and some regulatory context about Net Neutrality, please see: https://www.wired.com/story/fcc-wants-to-kill-net-neutrality-congress-will-pay-the-price/

For a brief analysis from a centrist news source, please see: http://thehill.com/policy/technology/362868-fccs-net-neutrality-repeal-sparks-backlash

Please make your voice heard, and share information widely!

Follow related tags:

blog blog-submission

Local Perspectives at Barnraising 2017

View of the marsh in the morning, as seen from my dormitory window. An egret basks in the sunlight.

As a 90's child in Houma, Louisiana, we would visit LUMCON on school field trips. I remember being charmed by the facility at a young age, a strange and seemingly out of place cement fortress at the end of the world, surrounded by wooden homes raised on stilts to protect them from rising waters. LUMCON has been the site of five Public Lab Barnraisings, in part because it exists at the very fringe of land and water off of the Louisiana coast, at the front lines of climate change in the United States. It's been about two decades since my first visit to LUMCON and the change in landscape is visceral and painful for me to acknowledge. It's been five years since the first Barnraising in Cocodrie, and the importance of Public Lab's work is made emminent when overlooking the receding marsh land and discussing the challenges we still face as advocates for a healthy natural environment.

LUMCON as seen on Google Maps. The amount of land loss is striking, as is the very linear canal across the bottom of the image which bisects the meandering natural waterways.

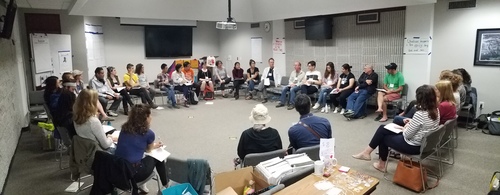

This year's barnraising brought together a diverse collection of knowledge - experts in their fields ranging from the Gulf coast to the Eastern seaboard, with representatives from the United Kingdom and China present to discuss the ways that we can continue to work collaboratively in order to better understand the environment and make scientific knowledge more accessible. Although everyone had their own specific question, or method for studying the environment, there was a common goal of creating an interdisciplinary, international network of citizen scientists and activists.

The weekend's agenda was built based on negotiating time and space for everyone's questions to be heard.

The ethos of the Barnraising is to address what knowledge is available within the Public Lab community, and how this information can best be disseminated to a multifaceted audience using a variety of organizing techniques. While a large amount of Public Lab's work is rooted in technology and development, there is an equally important foundation built on participatory science, community organizing, networking and power building. By taking an interdisciplinary approach to science and education, Public Lab promotes the capacity of each and every participant as a unique and invaluable asset towards furthering the goals of Public Lab as a community. On our first day at the Barnraising, Liz introduced a few mantras that encapsulated this sentiment perfectly, one of which being "EVERYONE HERE IS THE RIGHT PERSON."

Scott Eustis and a team of volunteers launch a Public Lab balloon mapping kit in order to create imagery of a nearby pond.

My prior involvement with Public Lab is minimal: I am trained as an archaeologist and a digital cartographer, with ancestral ties to the landscape of coastal Louisiana and an ingrained sense of stewardship for the cultural ecology that I was raised in. However, it was made apparent from the initial introductions and reading of the Code of Conduct that all sources of knowledge, ancestral or academic, were integral towards building an interconnected body of information and toolkit for studying the environment. The discussion frameworks endorsed by Public Lab incorporated the ecological, historical, social, and cultural backgrounds of all participants, and examinend the points wherever these bodies of knowledge and experience intersected.

The team deflating and repackaging the balloon, while confirming that the data collected covered the study area.

The Barnraising this year focused upon many issues that have increasingly impacted the quality of life for citizens across the globe for the past year. Some issues examined the natural environment, such as coastal land loss, lead and hydrogen sulfide poisoning, and the increasing number of oil spills and hurricanes, while other issues were anthropocentric, working to build strength through community organizing, raising support / funds, and democratization of data collection and tools for analysis. As a prerequisite for many sessions, the group would tackle major issues by unpacking issues down to their core, redefining common terms, and designing solutions based on publicly available resources. What is science, and why does the word have negative connotations? What is a community, and how do they define themselves?

Take-aways from the session, "How do we influence climate change deniers? / How do we make science cool?"

In each of session, regardless if it was discussion based or more tactical, the goal was to identify a problem, and then develop methods that will generate a better understanding of the issue. These discoveries should be recorded as data, so that others who share a similar curiosity can build off of an existing idea, set of code, or game design. Communicating data and results in an accessible manner, regardless of the audience's experience or background, was the central focus of every session that I attended.

@Rockets taking selfies of the group during a Barnraiser editing session using his DJI Spark drone.

In every interaction, there was a genuine feeling of admiration and respect for each other. The community established after spending three days exploring, building, kayaking, and sharing with others in a research center at the end of the world is a testament to what can be created when people come together around a common interest. In three short days, a group of 30 strangers gathered together to build a digital microscope and a weather-hacking antenna, while simultaneously solving the issues of climate change denial and lead contaminated soil in historic cities, forming friendships and connecting information.

Weather satellite antenna team, with sample hacked imagery behind them. From left to right: Gabi, Chase, Lyssa, Shan, and Tony.

I am inspired by the dedication and hard work exhibited by the Barnraising attendees towards each of their individual projects, and their willingness to contribute mental energy and emotional labor towards the disappearing landscape of coastal Louisiana. The struggle felt in the Mississippi delta is a result of an exceptional, uniquely self-sabotaging relationship between the land, water, and energy infrastructure that depends on depleting our resources for profit, however, our exploitative model of resource extraction has inspired others and spread. The gulf coast has felt the imminent crisis of climate change, rising sea levels, increasing subsidence, and more frequent hurricanes approaching for decades, and adaptation strategies are already being implemented in some of the most vulnerable communities. Our struggle is echoed in the environmental justice fights happening around the globe, and it is crucial that other cities learn from the successes and mistakes that have already occurred in Louisiana.

View from the tower of the surrounding marshland. One team of kayakers is just setting out on their journey, while another group walks towards an outdoors discussion.

The landscape of coastal Louisiana is historically volatile, and the people have adapted to the abundantly harsh ecosystem by forming a culture of resiliency and self sufficiency. I believe that these cultural values are reflected in the work of Public Lab, which operates in order to return authority and power to the groups of people who come together to build it. It is my hope that Louisiana will soon become a place for radical experimental development in coastal monitoring and restoration technology, so that lessons learned here can be utilized in other locales which are less prepared for life in a rapidly changing landscape. Public Lab provides an excellent framework for individuals from all walks of life to engage with the world around them using science, math, code, visual art, language, and storytelling as tools of inquiry. These open source, accessible tools are necessary in order to rapidly and thoroughly document a vulnerable landscape. Governmental organizations simply do not have the most important resource to complete the tasks at hand: they lack the sense of purpose, the ability to create place, and the inherent power residing in a group of people united.

Follow related tags:

balloon-mapping community louisiana conservation

What questions will you bring to the Barnraising? (Part II)

The Barnraising starts tomorrow morning! We're all super excited.

At the past two Barnraisings, in Morgantown, West Virginia ( #west-virginia ) and in Cocodrie in November 2016, I was able to interview and video folks who came, and ask them what questions they brought with them. This post is a continuation of my last, featuring Barnraising attendees -- and we're about to start this year's Annual Barnraising in Cocodrie!

Last time, I mentioned why I like this format:

I like asking this question because many people come with a specific need in mind, hoping to find someone from the diverse Public Lab community that may be able to help, and some come with knowledge, skills, and capacity -- and I'd wager that most people come with both of these! But finding ways to exchange knowledge, and support one another, is one of the keys to making an event like this work.

We've been sharing these with the tag #barnraisingQuestion on Twitter and Instagram. Please reach out with your own questions as you arrivein Louisiana today!

Leslie Birch

Hey, I'm Leslie Birch, I came from Philadelphia, and I was really excited to come to this particular regional barnraising because I'm interested in the problem of fracking that's going on because it obviously affects Pennsylvania as well as West Virginia. My big question is: is it true that they're using radioactive isotopes as tracers in the process of fracking? I'm still waiting to get that answer, but I'm excited about discovering it. I'm also wanting to figure out how I can use art and my knowledge technology and hardware to better communicate the problems that are going on in these ( @zengirl2 )

Matej Vakula

Hey, I'm Matej Vakula and I came here from Brooklyn -- I'm originally from Slovakia. I came here with a question of how to build infrastructures for sharing knowledge, and for knowledge production -- how to produce knowledge. ( @matej )

...

Ryan Covington

I'm Ryan Covington, from Washington DC. And the one thing I wanted to get out of the barnraising was to figure out how myself and the organization I work for, Skytruth, a small technology and conservation organization in West Virginia, can more broadly distribute our expertise, and satellite imagery and digital mapping to Appalachian communities and advocates that need it.

...

Follow related tags:

west-virginia cocodrie barnraising blog

Software outreach: a blog series

Since early 2016, Public Lab has worked to make our open source software projects more welcoming and inclusive; to grow our software contributor community in diversity and size. This series collects some of those strategies and initiatives.

I've written a bit before about software outreach at Public Lab, but I'm interested in taking a broad overall look at the specific strategies we've developed, borrowed, and built on since around April 2016, when we started this initiative. This will be a series, and I'll be collecting resources on this page. (Above: GitHub profile icons of some of our contributors)

What's this series for? A set of experimental new strategies and patterns for outreach have emerged over the past 2-3 years which are rapidly changing the landscape for newcomer engagement. I'm excited because they hold promise for more welcoming (and technically superior!) project growth which also support more diverse and equitable communities.

Starting point

We started out pretty "stuck," like many open source projects. From 2010-2016, we had only 16 contributors, total, 6 of whom were part of our Google Summer of Code programs (today we have over 100; we're still a small project, but growing fast). Our code was byzantine -- not because we were terrible coders, but because we were all busy, and we put new feature development before all else. Documentation, code cleanliness, install process, and even updating to the latest versions of our dependencies, all fell by the wayside as we made pragmatic decisions -- after all, I was the only consistent long-term developer, and I had something like 1/3 or 1/4 time devoted to this.

Our first foray into better onboarding was led by @justinmanley, one of our earliest and best GSoC contributors, who wrote this excellent post on how to reform and improve our code and outreach strategy. He did a huge amount to rework our code and systems to set us on the right track. With his help, we were ready for the next step...

SpinachCon

Three events led to our completely changing our direction. First, SpinachCon (in 2016), hosted by Shauna Gordon-McKeon and Deb Nicholson, was a great -- and humbling -- opportunity to try to get our code to be installable by newcomers. We'd estimated 30-60 minutes, after much work (even worse, in the past our GSoC students had sometimes taken more than a day to get dependencies installed!). We found several people who couldn't install our code at all over a couple hours. We spent a lot of time after that to get the install process down below 15 minutes, with an install video and a standard install environment in a free VM service, Cloud9, and things have improved a huge amount since then. Without this initial step, none of the following strategies would have worked!

First-timers-only

Second, in the spring of 2016 I attended a fantastic set of talks at BostonJS, which highlighted both the need for a wider conception of who contributes (including issue creators, commenters, etc) and, from Gregor Martynus of the Hoodie project, a whole new framework for thinking about building a contributor community. Click the link above to read more, and I'll be writing more about this soon, but I learned about the First-Timers-Only "movement", and really loved Gregor's attitude of "rolling out the red carpet for new contributors."

Diversity and project growth

It really seemed to me that Hoodie might even be more interested in recruiting and welcoming newcomers than in actually writing code! I was game -- writing a first-timers-only issue usually takes longer than solving the issue yourself. It's aimed at inviting someone new into the project, using a small but substantive issue to be solved as your initial point of collaboration, and as the start of a conversation and a relationship.

But I was wrong about one thing; as I learned in the coming months as we adopted this approach, a focus on first-timers really is an investment in the long-term growth of a community, both in size and diversity. It's a commitment to supporting people to take their first steps, but it recognizes that it takes work to do so, and that this work is totally worth it.

And in my mind, it emphasizes equity and diversity as core values, not only because they match our personal values, but because we recognize that they are fundamental to improving our work and ourselves. At the recent Google Summer of Code Mentor Summit, one thing I really appreciated hearing from a few people was that diversity was important to the success and growth of their project -- to incorporate new ideas and perspectives, and to be shaped -- transformed -- by them. It's a relief to hear people acknowledge that they're not just looking for someone to type out some code, but some insight, some human qualities, that they can't achieve without diversity.

Transformation

So, before we start diving into the actual strategies in subsequent posts, I'll say that one thing I've learned is that doing good software outreach means acknowledging that your own work must change. Not only in shifting from direct coding work to organizing and cultural work, but also in transforming your own coding style and even your project architecture (see Modularity, in an upcoming post) to make it easier for others to enter into your work and work with you. Good outreach will make you a better coder!

So thanks to everyone who's helped make this journey possible! I'm sure I'll be naming a lot of amazing people and projects as this series develops.

Up next: Friendliness, codes of conduct, and first-timers-only. Read more of this series on this page.

Also: do you have ideas or suggestions? We're seeking submissions for this series -- leave a comment or reach out to jeff@publiclab.org!

Follow related tags:

web-development software outreach development

Interview: Yvette Arellano

Lead Image from YES! Magazine

It seems fitting that the last interview we did in this series was with Yvette Arellano of Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (TEJAS). TEJAS is a Houston based organization. They are a small, but extremely mighty Environmental Justice group. With just five staff, they’re one of the most well known and respected organizations in the field. In their work, TEJAS is “dedicated to providing community members with the tools necessary to create sustainable, environmentally healthy communities by educating individuals on health concerns and implications arising from environmental pollution, empowering individuals with an understanding of applicable environmental laws and regulations and promoting their enforcement, and offering community building skills and resources for effective community action and greater public participation” (http://tejasbarrios.org/about-us/).

This interview was conducted in May, well before the tragic and terrible events of Hurricane Harvey. There is no doubt the events of Hurricane Harvey have stretched this group thin, and strained their many community constituents. TEJAS- Yvette and Deyadira Arellano, Juan, Ana and Bryan Parras, you and your community are in our thoughts. In solidarity.

Yvette Arellano interview below:

What kind of support do you look for for your community organizing activities?

When it comes to community organizing, anything from individual walking into the office, to funds to help us get the work done. We’re hoping there are young people looking to come in and help us with capacity for things like social media, and keeping the website up to date. We’re also looking for capacity through collaborations with schools, scientists, academics. We’re ultimately hoping to get more information out at a faster pace.

Also funding is a big one right now-- everyone’s crunched under this administration. Before we could count on federal funding, but now our organizations are trying to go after scraps that are left. Bigger organizations can see people laying down funds to support their work because they see what’s happening, but that’s not always the case on the grassroots level.

Are there any resources for your environmental work that you’ve found to be helpful? Such as guides, monitoring resources, websites, trainings, network, or otherwise?

We just got done working over past year with project with the Union of Concerned Scientists -- it’s a massive network with nothing but capacity. Together we got out the Double Jeopardy in Houston report.

The beginning of year was tough. We checked EJ Screen for missing information and the site went down for a solid week. It was a huge concern. We reached out to USC friends, they called up the ladder to ask why there was so much missing information. We also reached out to our friends in EJ community who gathered together and helped us download information from EJScreen and the Toxics Release Inventory so that we had it.

What were the strengths of these resources?

National Air Toxics Assessment is the most comprehensive source of information on cancerous toxins and amount of cancer on different parts of the country. It comes out once every three years, but it just released information in January regarding results from 2011. We went before NEJAC (The National Envioromntal Justice Advisory Council) and asked the EPA to have a more solid schedule for the data release for NATAData because we need it.

Different databases give us information that help us with our work. The TRI data (The Toxics Release Invintory) is the one that comes out the most frequently- annually. The National Emissions Inventory comes out every three years. Where TRI tracks what’s reported to come out of the stack, the NEI tracks fugitive and stack emissions. If there’s an accident - stuff that’s not supposed to come out NATAData grabs that all and pumps out numbers. ECHO (Enforcement and Compliance History Online) is a solid basis for grassroots groups to know what has been done and help community members. Finally, EJ Screen helps translate this all into graphs, and common language.

What do you these resources could have done for you, but didn’t?

They’re technical. EPA has addressed this by telling grassroots groups, or anyone, that there are technical assistance grants to help people. So you have to apply for a grant to get someone to translate it out of the technical jargon - and this is for a public database. It’s unfair.

When you, or your group, is learning something new, what is the best way for you to receive information? What is your preferred method of sharing information?

Just like anybody else - social media, email, news, and conferences. We also get together and share from our communities through regional meetings and phone calls. We also get out and do the old school block walking.

What methods of sharing or learning do you or your group find challenging?

Navigating datasets and databases with older people who aren’t used to it is challenging. Also translating from English to any other language is something that’s a barrier as well.

Would being in a network of people from different backgrounds discussing environmental questions and collaborating on how to address them be useful to you? If so, in what ways?

Yes, 100%. I think working with different organizations from different backgrounds and populations is important. We need to be able to communicate with their groups, and they with ours. We have more experience with these issues when we work together so we need to make a vast network of people to deal with these issues.

What would you want to be able to do, find, offer, or receive through interacting with this network?

Ideally, I would want to be able to piece the puzzle together faster. Pipelines through Illinois are going to connect to Texas and to Louisiana refineries. That’s very similar to so many parts of the country. Across region or nation we have these joint issues. We could work together. We could reach a solution together and create mass momentum across a nation.

Who would be important people for you to be able to engage with?

I see the space being populated with scientists -- that’s new, we’re not used to scientists and academics opening their eyes and seeing challenges our communities face. Opening that space and really uplifting that message against the administration. We need legitimacy as grassroots organizers. We’re not seen as having the most legitimacy, but when scientists come in and support our message with data it’s really helpful. It’s also really important for young environmental justice organizers to connect with elders. We live in age of technology. If we can’t share those skills, we’ve already lost.

What would be important values or practices for the networking space to hold?

You’ve probably already heard this. Jemez principles of engagement. Environmental Justice principles are about being open and inclusive. Letting people -- community -- speak for themselves. Committing to self-transformation. At the end of day, we’re struggling, and we should be aiming at a joint approach. There is power in numbers.

End of inteview

Thank you Yvette!

It has been a wonderful journey learning from amazing grassroots and environmental justice organizers over the past several months, but that learning doesn’t stop with the end of this series. I’m wondering for those who have read and followed along:

- What questions are you left with?

- What surprised you?

- Where do you see steps forward?

- Who else should be brought into this conversation?

Comment below!

Note on Harvey Recovery: You can support TEJAS in response to Hurricane Harvey by donating to A Just Harvey Recovery Fund here.

Other avenues to share and help on Public Lab:

- Support Gulf Restoration Network’s efforts to capture and report pollution events from Hurricane Harvey by sorting through aerial images in this activity.

- Public Lab has organized Harvey related material on this page where you can ask questions and offer support.

**This post is part of a series with Grassroots and Environmental Justice Community Organizers. Read more on the series here or follow the blog tag to get updates on new posts.

Follow related tags:

gulf-coast interview blog grassroots

Interview: Jim Gurley

Lead image from the StarTribune, photo credit Brian Peterson. An uncovered frack-sand stockpile (“Mount Frack”) in downtown Winona, 2013. In the background is the historic Winona County Courthouse. (After large demonstrations and direct action at Winona’s City Hall, the city finally reacted to the citizen’s demands and required the carcinogenic frack sand to be removed.)

The frack sand industry (sometimes spelled frac sand - sometimes considered the industry’s spelling) is one of the lesser known dirty supply lines of the oil and gas industry. “With the massive adoption of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling in the U.S., round silica sand is needed as a ‘proppant,’ a material used to prop open oil and gas-bearing fissures while also allowing gas and oil to escape.” (read more on the history on the Frac Sand wiki). For many years Wisconsin and Minnesota, among other midwest states, have been the victim to the oil and gas industry’s long and vicious assault on natural resources through the frack sand mining industry. Think of the lands where Aldo Leopold wrote the famous Sand County Almanac. These are the beautiful places that have been pillaged. Hills have been flattened, rivers have been silted, farmland have been destroyed, livelihoods have been threatened, and human health impacts have been disregarded.

But out of this chaos and injustice, again we find incredible people who are working together to bring light, and fight back. The interview below is with Jim Gurley, one of many we have to thank for their hard work against the oil and gas industry on the Midwest front.

Jim Gurley Interview Below:

What kind of support do you look for for your community organizing activities?

I split my time between two issues: frack-sand mining, since 2011 with CASM, (Citizens Against Silica Mining) and exploding oil trains, since 2014 with CARS-Midwest, (Citizens Acting for Rail Safety). I’m also active with LSP (Land Stewardship Project). I also plan to help as an organizer with Our Revolution-Minnesota. The groups I’m a part of have not done much fund-raising. We’re all volunteers, except for a staff member or two at LSP. So financial support is not something we have focussed upon.

For rural issues in our county, we lobby for support from our county board of commissioners. The only way we were able to secure a ban in our county on frack sand mining operations (the first and only such ban in the U.S.) was because we spent a lot of time, energy and money (we did fund-raise for that campaign) to get one of our CASM members elected to the board. She won and replaced a pro-sand person, who was a lifelong resident of Winona, and was a TV and radio news anchor with virtually 100% name recognition. Her win was extremely important -- it helped us get the ban (flipped the majority on the board from 3-2 pro-sand to 3-2 against) but also provided the first and only “referendum” of sorts on the frack-sand issue, so we had something tangible to point to when discussing public opposition to the mining. Frack sand is a dangerous carcinogen, so we are interested in low cost monitoring of dust, and ways we can measure particulate matter around the seven frack-sand operations in the city of Winona.

In CARS, we seek and get support from public officials at all levels, and we have networked with other groups who are fighting oil trains throughout country. Those sorts of connections are important. Perhaps the most important support we look for is from local citizens who write Letters to the Editors, come (and sometimes speak) at hearings, attend our meetings, march in direct action, etc. “People power” is our most effective and valuable resource.

Are there any resources for your environmental work that you’ve found to be helpful? Such as guides, monitoring resources, websites, trainings, network, or otherwise?

Several CARS members attended the Oil Train Response conference in Pittsburgh, and that was very informative and good for networking. The human capital of good researchers in our own groups, as a resource, is key for us. Working with the staffs of senators and congressmen has been somewhat helpful. The Crude Awakening network holds a national conference call every few weeks, and that allows us to get good and timely information about victories and bad things around the country. We need to bolster ourselves and each other and take time to celebrate and integrate the victories that we do have. Connection with others is a reward.

When you, or your group, is learning something new, what is the best way for you to receive information? What is your preferred method of sharing information?

In our frack sand group, some members are not on Facebook, and a few don’t have email. So we use phone calls and emails. Short emails are good, but group email discussions (which can easily devolve into what I call “e-maelstroms”) are challenging. Emailing information prior to meetings allows informed comments at the meeting. In-person contact is paramount.

Someone with expertise willing to visit and address our group is a great way to learn. We’ve also sent a representative to workshops and seminars. One important thing to me — as both a listener and a presenter -- is to be able to clearly hear and understand the person speaking (particularly considering that many volunteers are elderly and hard of hearing). Testing acoustics and microphone ahead of time, and asking at the beginning of the presentation if folks can hear, can make all the difference. It also helps in getting good audio when we are video-recording an event.

What methods of sharing or learning do you or your group find challenging?

New social media platforms are challenging. I and others find Facebook to be useful, but not all of us are on Facebook. We've found language barriers. Reading something that is above our skill level containing technical jargon is difficult; e.g., reading an industry journal is sometimes hard to “translate" into vernacular English in order to report about it to the group. This also happens when working with scientists, or people who have a specific expertise. Articulating scientific ideas in layman's language is a skill and talent that should be cultivated by those who wish their knowledge to be widely understood.

Would being in a network of people from different backgrounds discussing environmental questions and collaborating on how to address them be useful to you? If so, in what ways?

Working with a diverse group of people (geographical, gender, racial, ethnic, education, political party, age, etc.) gives us complementary skill sets and perspectives. We need to have folks who like to make phone calls, others who like to do on-line research, others to write op-eds, etc. Bringing people together from different political backgrounds is challenging, but important and potentially rewarding in the long-term, if we are sincere and honest and open-minded. Having a wider group or network of people who could be resources to each other and develop a broader expertise would be great.

Who would be important people for you to be able to engage with?

I would like to engage with (and educate) elected officials about environmental issues. They often are well-versed in how to create jobs, but they need to be at the table to learn about environmental issues and the consequences of the job-growth they advocate. It would also be useful to have academic folks there, but so far, few academic leaders at public universities have been willing to help us in a public way due in part to pressure from the state. Last, scientists and activists sharing a space where they could share with each other what they’ve learned could be really useful as well.

What would be important values or practices for the networking space to hold?

Tolerance, patience, and focussed listening are important values. Sometimes people new to activism may be turned off if someone is impatient with them or they don’t feel welcome, so having a welcoming culture is paramount. Follow-through is also key, and it’s healthy for a group to respectively hold members accountable for what they have promised to do. On a mechanical level, ground rules and an outline of shared expectations can help protect these spaces.

In physical shared spaces, welcomers at the door are helpful. Also, we need to be intentional about celebrating our victories, and to avoid getting too intense at meetings. We need to be able to laugh at ourselves and be lighthearted at times. Otherwise, stress and the resulting burnout can hurt our efforts.

End of interview

Thanks again Jim! Hearing about your work is truly inspiring.

**This post is part of a series with Grassroots and Environmental Justice Community Organizers. Read more on the series here or follow the blog tag to get updates on new posts.

Follow related tags:

interview blog silica frac-sand