The Public Lab Blog

stories from the Public Lab community

About the blog | Research | Methods

What fuels a movement?

Lead image of protesters protesting the Pet Coke Piles on southeast side of Chicago. Image found on the Public Lab Chicago page.

Passion alone is not enough - we need to be great organizers

Thanks to Olga Bautista for the title of this blog post, please read on for the transcript of my interview with her.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Public Lab’s relationships with community organizers and local grassroots environmental groups. Over the years, there have been a number of people and groups who have put “boots on the ground” and conducted local environmental research projects. Many of them have worked to create physical space and events in their community for Public Lab gatherings. Yet the stories of their work come back to the broader Public Lab community through word of mouth rather than through these activists directly engaging with online spaces. Ultimately, in my opinion, if we’re seeking Public Lab to become a space for people to collaborate on and publicize their environmental projects, these on-the-ground people are who we should be thinking of and creating both our in person and our online spaces for. I want to start learning more deliberately from some of these community organizers about what is working, what could be better, and how can we amplify the things that they want to be heard.

To kick off this exploration, I had a phone call with Olga Bautista. I’ve known Olga for about a two years. She is a rock star community organizer. She (and Benjamin Sugar) were the driving forces behind the second Regional Barnraising in Chicago. For years now, she and her group, Chicago Southeast Side Coalition To Ban Petcoke, have been working to fight the petroleum coke piles in their community that sit directly in their neighborhood and on the Calumet River. Due in large parts to their activism and efforts, these piles were just recently moved from their community.

It had been a while, so I wanted to catch up, hear what has been going on, how they’ve been doing, and see if I could explore some of the questions I’ve been having about the Public Lab space with her. Below is an excerpt of our conversation. Olga was kind enough not just to give me some advice about the questions I’ve been floating around, but to really give me a low-down on things that have been useful for her on an organizing level in the past year as well. Thanks Olga! Here’s the transcript:

Olga Bautista, of the Southeast Environmental Task Force and the Southeast Chicago Coalition to Ban Petcoke. (Photo by Terry Evans / Courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Photography)

How have things been going?

Things are changing for the better, but we need more people, and we need to be intentional about building more leaders who can take on more of the work. It’s important that we’re deliberate in who makes the decisions. We don't want the big greens or other advocacy groups to speak for us because we know exactly what would make our lives better.

What are some of the challenges you have been facing lately?

It’s complicated figuring out who are the other players on the playing field and plowing through anyway. It’s also hard to not get discouraged. There are a lot of groups who work on the issue, people who break off forming other groups, and we end up competing with others who are working on the same issue.

What are some of the things that have been important in your successes?

It’s really important to plan and evaluate everything. For example, before meetings we talk about what we want to achieve, after we talk about what has been decided and we check in with everyone about how they feel it went. We’ve been starting to use this methodology that really centers us and we have been doing things this way for about a year. It's organized, and it has helped us work hard and be really intentional about everything we do.

Some of the things we practice are that:

We make a point to sync up in the beginning and at the end of every meeting, to see how we feel about the work we did. We have a vibe watcher at our meetings, when you have that kind of order, it makes everyone feel comfortable that they're getting heard. We’re also really well prepared before meeting. Leaders will set the agenda ahead of time and send out materials. Everyone is expected to have reviewed everything prior to coming to the meeting.

It’s really professional. We’re grassroots organizers in a working class community, and we’re really figuring this out and it’s working.

What has been challenging for you?

Some of the things in my case that have been difficult, are things like managing time and calendars. We have so many different challenges, linking them up and planning time to reflect on the work that we're doing is tough. I'm not able to carve out enough time for this. It's easier for me to go to a meeting than carve out time in front of a computer. Because I’m a mom, I’ve got these other responsibilities and pressing things that take up my time.

Another challenging thing is that if you're an organizer that lives in an affected community, it’s different than if you live in a different neighborhood. If you live somewhere else you can separate out your life. I run into people just going to the grocery store, people who ask me questions about emails or who get mad and are violent to me about the work I do with the coalition, and I’m just trying to pick up a jug of milk!

How has your work and relationship been with Public Lab?

With Public Lab, I talk about you guys all the time. All your ears should be ringing, because it's part of the message. Public Lab is an extremely important part of the petcoke fight. Balloon mapping was absolutely important. To see everyday people get together and gather this extremely important data without having to get in a plane. We literally had an entourage following us sometimes.

As a community organizer, what are some things you need or look for when you start to work with other groups or organizations?

One group I’ve been working with lately that has helped a lot with some of these community trainings had stipends for me to do a week long organizer training. This made a huge difference. I’m looking for support in things like grant writing, and groups who collaborate with other agencies and foundations who might be able to help us fund the work.

What’s coming up for you in the near future?

In the next three weeks, we’re working to develop a door knocking campaign. It’s something we haven't done since we started, but we really want to do this again. We need to find new leaders. We need to figure out who is serious, have a plan for those people to go to training and learn about things like structural racism, and structural oppression. These are ideas that we know and feel their affects everyday. Some people just don't know there is a name for it.

What would tell others who are just getting into Environmental Justice issues and community organizing?

There are so many things to learn and practice:

1) Skills to be efficient and effective are not just common sense, you need co-conspirators in your group who are on the same page and you need to practice those skills.

2) Nobody told me that the work is based so much on relationships. You have to develop relationships with people. I’m doing a lot of one-on-ones now, which some of us get trained on. Things like: when you meet someone for the first time, you don't end the conversation with an ask. Those are some of the things we have been learning.

3) It’s slow process and can't be rushed. This is difficult for me. We have deadlines. We have comment periods coming up, having regular expectations of each other that we need to accomplish. I always have feelings like I’m not able to follow through or i’m not depending on other people enough.

4) Getting the people on the same page with you that's difficult, that's the relational part. People have to take on the work fully. Everyone I talk to, they have to do it for themselves, not for me.

5) People on the ground, we need to have exit plans for things that we are committed to that are not going anywhere and take things off our plate instead of put things on.

-- End transcript --

I learned so much from this conversation with Olga. I’ve been really inspired by the work she does and what the group has been able to accomplish. While I can start to see some future directions come out of this conversation on the questions I had, I don’t want to jump to conclusions until I have a few more conversations and things to draw from. I would l love to hear if you have ideas on this topic, or if you know anyone I should share this conversation with. Let me know who in the comments below or email me at stevie@publiclab.org. Looking forward to it!

Follow related tags:

blog petcoke chicago pm

Interview: Chris Nidel on environmental evidence in court

A few months ago, as our first interview for the Environmental Evidence Project blog series (#evidence-project), we caught up with Chris Nidel, an attorney with Nidel Law, PLLC, based in the DC area. Lead image: satellite images of waste at a Maryland Perdue chicken farm from a case Chris fought in 2012.

_

_

As Chris writes in his bio, he's been involved in environmental law for a long time, starting shortly after getting a Master's in Chemical Engineering at MIT:

After graduate school, I went to work for a major pharmaceutical company doing drug process development. After a few years, I became disillusioned with the approach that the pharmaceutical industry, including the company I was working for, took toward putting profits over saving lives.

...

The combined realization that this company seemed more concerned about profits than creating cost-effective lifesaving medicines and that they seemed to care less about the illness and death that they were responsible for in their own right, forced me to leave. I went directly to law school at the University of Virginia. After graduating, I relocated to Dallas, Texas so I could work on major environmental and toxic tort litigation with the late Fred Baron at his firm Baron and Budd.

In the years since, Chris has worked at different firms and eventually started his own, and has been part of cases involving "cancer clusters, unsafe landfills, and air and groundwater contamination", and "air pollutants from TVA's coal fired power plants in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Alabama."

With all he's seen and done in environmental law, we wanted to ask some general questions about how evidence is used in court, from a pragmatic, real-world perspective.

I get this question all the time, where somebody says "how do I take samples that'll be admissible in court" -- and unfortunately, there's no right answer. ... I've had defendants in cases challenge EPA's own historical sampling. So you can have EPA scientists take samples and send them to whatever lab they feel is the appropriate lab to do the analysis, with whatever certification they have, and then the big company still comes back and say, "well, we don't believe those sample results. So while there is no silver bullet, the key is the reliability and ultimate credibility of the results. If the sampling and analytical methods are defensible...the data should be admissible"

Chris is realistic about the shortcomings of the current system, and emphasizes that you can never be 100% sure that evidence will be admitted, or that it will be effective:

Any time there's a legal argument in a court, there's always a chance that you'll lose it. If somebody said to me, "I want make sure I'm guaranteed that these samples -- or this evidence, or data -- is going to get admitted into court, I would be a fool to say, "sure, here's what you need to do guarantee it," because there's no guarantee. If you file a case against Monsanto, and the judge happens to play golf with the vice president of Monsanto, you may not be able to get those samples in. These issues may be out of your control and are independent of who did the analysis, and what qualifications they have, and what protocols they followed.

Data without advanced degrees

Chris has, however, worked on a case with Waterkeeper Alliance where samples were collected, stored, and managed by someone without a formal scientific degree. In this case, the person collecting samples was member of the local Riverkeeper organization and was an environmental advocate, but did not have extensive scientific training. Rather, she had a web-based certification for water sampling. According to Chris,

...the more important thing was that she actually followed a protocol. She got sterilized sample bottles from the lab, she wore sterilized gloves when she took the samples ... she filled out the chain of custody, she took it to the lab within the specified amount of time, she kept the cooler on ice, whatever was needed. And that was it. She took it to a lab, and they followed certified protocols. We didn't hire an engineer, or a chemist or a biologist to go out there and we didn't need to.

Due to this sampling protocol and detailed chain of custody, and since the laboratory followed an established analytical protocol, the samples were admitted as evidence in court without issue. In fact, the validity of the samples themselves wasn't even questioned in this case. Demonstrating the use of well-documented and rigorous methods can sometimes be sufficient for samples and data collected by non-accredited persons to be accepted as court-admissible evidence.

Clearly, there are nuances to this, and even without a cookie-cutter approach, there are pathways for people without a scientific degree to produce knowledge in ways that can be legally recognized. But that's what can be so frustrating about this topic -- it's not a clear set of rules you can just follow, and even if you follow what rules there are to the letter, you're still not guaranteed a result.

Expert witnesses

The example above specifically deals with samples that were analyzed later in a lab. What about other pathways? Many, it turns out, involve some kind of expert witness to authenticate, or essentially vouch for, the evidence. The judge or jury, who may not have relevant formal backgrounds to evaluate the evidence, won't be, as Chris puts it, "sitting there trying to speculate as to why they should believe one over the other" -- they'll rely on experts for that sort of thing. But who chooses the experts?

The problem with those experts are they are going to be paid by both sides. Clearly, they're going to have an opinion that's in your favor, and the other side is going to come in with an opinion in their favor, and... if you thought the DNC was bad, that's the sausage being made.

Not to mention -- what qualifies someone to be an expert in court? How much do expert witnesses tend to cost, and what happens if one side or the other can't afford an expert witness? We hope to circle back to this question in a later post.

_

_

Chris spoke at our June 6 OpenHour online panel on the topic of "Concepts of Proof" -- where he discussed his use of aerial photography in pollution cases. Watch the full video here.

Photographic evidence

Looking for a way through the thicket, we were really interested in photographic evidence, and how it might be different -- does it require expert authentication too? Chris said that it depends:

What conclusions or facts are you trying to establish? In our PCB case we used a lot of historic aerial photos... and EPA had an aerial photo lab assess the pictures -- here are barrels, etc, here are contours.

So interpretation by experts can enter into it. But what's most important is how it fits in with, and can relate to, other supporting evidence. One key aspect appears to be whether or not understanding a given piece of evidence is common knowledge, or if it requires certain training and experience to understand the implications of that evidence. Chris talked through a scenario we mentioned in #OpenHour about a photograph taken by a crane operator, who documented a plume of suspected pollution in a nearby waterway:

If you just put the guy in the crane on the stand, and you say, "You were up in the crane, you took these pictures. How did you take them? On what day? What were you looking at? Explain to us what direction you were facing when you took the pictures." [Because] the guy who sat in the crane who doesn't have any background, you probably don't get anywhere with it. You get the fact that there are pictures; you might even get them admitted. You might get the jury to be able to draw their own conclusions:

"I took the picture, I was on top of my crane, it's about 200 feet up, I was looking at the South Bay and this is what I saw."

The jury can look at that picture and they can understand that. Everything is good up to that point. Now, "I think this looks like a bunch of chromium was thrown into the bay. I'm just a crane operator, [but] my conclusion is that a bunch of chromium was going on in the bay that day."

That probably doesn't fly because neither the guy in the crane or the jury could conclude that it's necessarily chromium. On the other hand, if you can get that in front of the jury and the judge says, "I don't know that Johnny in the crane can tell us it's chromium, but I think it's admissible," and the jury could make their own deduction that there was chromium because you have other evidence. Let's say that you have evidence of what was in the barge from which the plume was coming. Now we have test data that shows that the barge was full of chromium, and now you have a photograph from Johnny in the crane that looks like a bunch of stuff is coming out of the barge, ergo, the jury decides chromium came from the barge.

You can also hire an expert and then the question would be does that expert have something that will help the jury themselves that the jury doesn't have without the expert? The expert comes in and says, "I've seen lots and lots of chromium discharges from power plants and I know what chromium looks like when it gets discharged, and this is clearly a chromium discharge." Then you get at it that way as well, and that's probably the typical way to do it, albeit the expensive way to do it. You hand off those pieces of evidence to someone else to draw the conclusion that you want to draw for the jury.

Given the complexity and uncertainty of the law as it plays out in court, we found it very helpful to hear about specific cases and examples. It seems that permissible and influential evidence is in the eye of, well, many beholders. While sometimes it may depend on internal, potentially invisible relationships between a judge and the case at hand, other times it's about walking a jury through enough solid testimony for them to draw conclusions about the value of the evidence themselves.

There are a few things we have learned to that can help us strengthen our cases as potential curators of evidence. We can make sure we're following existing protocol, as seen in the Riverkeeper example. We can also secure supporting evidence for our claim, such as seen in the crane operator example where supporting evidence could come from a lab or an expert witness.

Our hope is that in that the posts to come, more of these pathways to success, and limitations around evidence, are teased out. In the meantime, let's continue these discussions here and ping in with your questions and ideas. Thanks to Chris for making time to talk with us!

Questions

Questions we've addressed here:

- How is environmental evidence admitted into court-based legal processes?

- What can strengthen the case for evidence to be admitted in court?

- Who can vouch for, or interpret, evidence in court, and how is it weighed?

- Is photographic evidence treated differently from other environmental evidence in court?

- ...

Questions we'd like to address in upcoming posts:

- What collection, storage, and analysis protocols can strengthen environmental evidence in court?

We're moving these questions into the new Questions system -- so feel free to repost one here:

| Title | Author | Updated | Likes | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How do you merge GPS logger data into photographs? | @warren | over 6 years ago | 1 | 11 |

| Who can vouch for, or interpret, evidence in court, and how is it weighed? | @warren | over 7 years ago | 1 | 0 |

| What are the limits to what can be interpreted from a photograph without an expert witness? | @warren | over 7 years ago | 0 | 0 |

| What are ways to strengthen photographic evidence in court? | @warren | over 7 years ago | 1 | 0 |

| What's the best way to archive/store a timelapse video? | @warren | over 7 years ago | 1 | 3 |

Follow related tags:

evidence blog legal openhour

A message from the Public Lab staff

Public Lab resists and rejects: racism, sexism, ableism, ageism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, body shaming, religion shaming, education bias, and bullying.

We do not tolerate hatred towards women, people of color, LGBTQ or based on religious belief. We stand by our community and partners and are committed to continuing our work on environmental and health issues affecting people.

Follow related tags:

blog

Thoughts on Method 9 and its utility

Several people in our Public Lab community are concerned about various kinds of airborne emissions, and what we as the public can do about them. One of the most accessible methods for assessing emissions is to estimate the opacity of emissions (I’ll explain a bit about this below) using EPA’s Method 9. Some community members have gone through Method 9 training and have found it very useful; others have found that it hasn’t been useful for their situations. I recently went through the training and became certified for Method 9, and I want to share some of the things I learned in that process, and my thoughts about the potential utility of Method 9 for various situations and concerns. Please comment and share your thoughts too!

What is opacity and what is Method 9?

Opacity is the extent to which light is blocked, or the extent to which you can’t see through an emissions plume. Opacity is caused by small particles and gases that absorb, reflect, or refract light. Particles that are similar size to visible light wavelengths (390-700 nm) can scatter visible wavelengths effectively, muting light rather than preferentially reflecting a given color; carbon particles (like soot) effectively absorb light, largely contributing to plume opacity.

Method 9 is a method to standardize the direction and distance from which you observe an emissions plume, with regards to both the plume direction (related to wind direction), sun direction, and stack (or pile) height. The basics of this include that the sun needs to be at your back, you need to be looking perpendicular to the plume, and you should be between “3 stack heights” (or, three times the height of wherever the emission is coming out or off of the source) and a quarter mile from the source. These guidelines can be very tough to follow, however, given potentially limited access to unobstructed views of the emissions source. Method 9 recommends that you monitor emissions in the morning or afternoon -- not midday -- and move if the wind suddenly changes direction. Again, this is easier said than done, especially if you are not directly on the property where emissions are occurring. The training for Method 9 includes a lecture component and field training where you practice estimating the opacity of plumes, training your eyes to discern smoke opacities to ~5% resolution.

Starting as early as 1859 (in the City of New Orleans vs. Lambert case), smoke opacity has been used to regulate air pollution. Today, states regulate plume opacity for point-source emissions (like from smokestacks) and most regulate opacity of fugitive emissions. Common opacity limits are 20% opacity, which means that 20% of light is blocked, or you can only see through the plume to see 80% of the background behind the plume. In practice, 20% opacity is visible, but can be hard to differentiate the bounds of the plume -- it’s really not thick smoke. Method 9 is used to measure opacity and enforce state emissions opacity regulations; if you are certified in Method 9 (which anyone can do), you can report violations and prompt an enforcement response.

What are some of the limitations of the method?

Method 9 can be very useful, but also has many limitations.

First and foremost, Method 9 only allows you to assess visible emissions -- it provides no ability to ascertain the chemical composition of what is being emitted, and is not useful for most vapor emissions.

Steam plumes are a significant complicating factor too, as steam is not subject to opacity rules, and it is often difficult to distinguish whether or not a plume contains steam or not.

The physical restrictions of conducting Method 9 also limit its utility since it is often not possible to view plumes with the specific siting requirements mentioned above.

A significant limitation of Method 9 is that there is no residual evidence of the visible emissions observed, which can limit agency’s ability to enforce violations. It is recommended that people conducting Method 9 also take photographs of the site and the emissions to document what was observed. There is also a digital camera alternative to Method 9, which has its own limitations, and is discussed below.

Another limitation is that persons need to be re-certified every 6 months, with each certification training/test fee ~$200. In some places, this fee is waived for citizens and covered by permit fees for industry, but in most places each person is responsible for paying their certification fee, and can be exclusionary to people who can’t afford that.

What about fugitive emissions?

In some states, like Wisconsin, opacity limits apply to fugitive emissions too. Fugitive emissions are any emissions from a process that are not through a specified emissions point -- they are construction dust plumes, dust kicked up from unpaved roads, wind-blown dust coming off of sand piles, plumes emanating from blasting, etc. Assessing the opacity of fugitive emissions can be complicated since there often isn’t a distinct plume with a distinct direction, but as long as you are looking through the narrowest/shortest dimension of the emissions, and are following the proper siting requirements (i.e. sun at your back, appropriate distance from emissions point), Method 9 assessments are valid for fugitive emissions. Since fugitive emissions are more sporadic and variable than smokestack emissions, it is recommended that you become familiar with the characteristics of those fugitive emissions before starting your monitoring. It is useful to check out your state’s regulations before starting monitoring too, since some states, like Colorado, unfortunately have exemptions from opacity rules for fugitive emissions.

Where can I learn about emissions opacity regulations in my state?

Visible emissions opacity limits are included in each state’s air pollution regulations. Usually these regulations are searchable online in each state’s administrative codes on the state legislature website. Opacity standards are also included in the “State Implementation Plan” (SIP) which the state develops to detail how the state will achieve the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS). Legislative websites and SIPs can both be somewhat onerous to navigate, so it may be most efficient to search for “opacity” on your state’s environmental agency (usually a DEP, DEQ, or DNR) website.

What are some similar methods?

There are four other methods recognized by EPA that are similar to Method 9.

Alternative Method 82, also known as ASTM D7520, is the “Digital Camera Opacity Technique” (DCOT) that can be used in place of Method 9 when approved. Note that Alternative Method 82 is only approved to demonstrate compliance (or lack thereof) with federal opacity limits, but not opacity limitations set by the state or municipality. Alternative Method 82 does have the advantage of having a data record of visible emissions, however, it can be very difficult to actually conduct. First, the DCOT system, which includes a digital camera, a photo analysis software platform, and a results assessment and reporting component, needs to be certified, and this certification process is more arduous than that of Method 9. The DCOT operator has to complete a manufacturer-specified training course, and follow all of the Method 9 siting requirements (and a couple of additional limitations), and then the images also generally have to be sent to a third party for analysis. Also, as of today, there is still only one DCOT system that is commercially available and certified to conduct Alternative Method 82, and the software licenses can be thousands of dollars per year. In addition to the cost for the DCOT system and analysis, it also takes longer, and cannot immediately identify opacity violations (it takes processing time). Therefore, while there are some definite advantages of Alternative Method 82 (notably the data record with photographs), there are currently considerable drawbacks. The company whose training I took, AeroMet, recommends that the EPA address these drawbacks to make the method more accessible and feasible for people to actually use.

Methods 203a, 203b, and 203c are alternative methods for Method 9 for slightly different types of opacity limitations: time-averaged, time-exception, and instantaneous limitations, respectively. Each of them are the same general procedure, but in 203a total time assessed can be 2-6 minutes (whereas Method 9 requires 6 minutes), 203b averages the amount of time that emissions are above the opacity limit, and 203c takes observations every 5 seconds for 1 minute (whereas Method 9 takes observations every 15 seconds for 6 minutes). For Methods 203a-c to be acceptable for assessing compliance with air pollution regulations, that must be specified in the state implementation plan.

Method 22 is somewhat similar to Method 9, but is used to assess the frequency of visible emissions, not the opacity of those emissions. Method 22 is mostly used for fugitive emissions and gas flares. In Method 22, the observer uses two stopwatches, one to measure total time elapsed, and one to measure the time when visible emissions are present, to determine the frequency and percentage of time that a source is visibly emitting. For Method 22, the observer can be indoor or outdoor and there are fewer siting requirements overall. If industries are subject to compliance assessed by Method 22, it will be stated in the SIP.

Follow related tags:

plume epa air-quality blog

Enforcing Stormwater Permits with Google Street View along the Mystic River

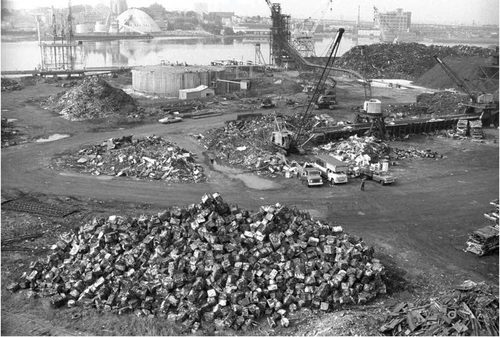

Compressed autos at Mystic River scrap yard, Everett, Massachusetts, 1974. Spencer Grant/Getty Images. CC-NC-SA

In 2015 the New America Foundation asked @Shannon and me to write a chapter for their Drone Primer on the politics of mapping and surveillance. I worked in an example of positive citizen surveillance by the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) that I’d heard about in a session at the 2015 Public Interest Environmental Law Conference. I’ve excerpted and adapted my writeup of the CLF case as a part of our ongoing Evidence Project series. If you know of similar cases please get in touch!

Geo-tagged aerial and street-level imagery on the web can be a boon to both environmental lawyers and the small teams of regulators tasked by US states with enforcing the Clean Water Act. Flyovers and street patrols through industrial and residential districts can be conducted rapidly and virtually, looking for clues to where the runoff in rivers is coming from. Combining aerial and street-level photographs with searchable public permitting data, the 1972 Clean Water act’s stormwater regulations are now more enforceable in practice than they have ever been (Alsentzer et. al., 2015).

State and federal environmental agencies often do not have time or resources to adequately enforce permits under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) that regulates construction and industrial stormwater runoff, and roughly half of facilities violate their stormwater permits every year (Russell and Duhigg, 2009). Enforcement can be picked up by third parties, however, because NPDES permits are public. Plaintiff groups and legal teams conduct third-party enforcement through warnings and lawsuit filings. Legal settlements from lawsuits recoup the plaintiffs legal costs, and can also include fines whose funds are directed towards community-controlled Supplemental Environmental Projects that help improve environmental conditions in the violator’s watershed. The Conservation Law Foundation (CLF), a Boston-base policy and legal non-profit, operates in precisely this manner, recouping their costs through lawsuits and directing funds to Supplemental Environmental Projects in the Mystic River Watershed.

In 2010 a neighborhood group approached the CLF about a scrap metal facility on the Mystic River. Observable runoff demonstrated the facility had never built a stormwater system, and a quick US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) NPDES permit search revealed that they had never applied for or received a permit. The facility was flying under the EPA’s enforcement radar, and so were four of the facility’s neighbors.

Between 2010 and 2015 CLF’s environmental lawyers initiated 45 noncompliance cases by looking for industrial facilities along waterfronts in Google Street View, and then searching the EPA’s stormwater permit database for the facility’s address. Most complaints are resolved through negotiated settlement agreements, where the facility owner or operator funds Supplemental Environmental Projects for river restoration, public education, and water quality monitoring that can catch other water quality criminals. Together, CLF and a coalition of partners such as the Mystic River Watershed Association, are creating a steady stream of revenue for restoration, education, and engagement in the environmental health of one of America’s earliest industrial waterways.

Regardless of their effect, legal threats are stressful, often expensive, and can take years to resolve. Even when threatened polluters are acting in good faith to clean up their systems, the process of identifying and persuading companies to comply with environmental regulations can be strain relationships in communities. Non-compliant small businesses on the Mystic River that have been in operation since before the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972 may never have been alerted to their obligations under the law. Their absence from the EPA database reflects mutual ignorance from bureaucrats of businesses and businesses of bureaucracy. However, businesses bear the direct costs of installed equipment, staff time, and facility downtime, indirect costs of professional reputation from delayed operations or identification as a polluter, and transactional costs of paying for legal assistance or court fees. Indirect and transactional costs are hidden punishments that can accrue regardless of guilt or readiness to comply.

To combat the negative perceptions that can accrue from the use of legal threats, CLF proactively works to fit itself into a community-centered watershed management strategy. CLF and their partners run public education and outreach campaigns and start with issuing warnings that aren’t court-filed (Alsentzer et. al., 2015). Identifying and working with businesses operating in good faith is a tenet of community-based restoration efforts. By using courts as a last resort and participating in public processes where citizens can express the complexity of their landscape relationships, CLF and their partners are increasing participation in environmental decision-making and establishing the legitimacy of restoration and enforcement decisions.

Regulations and permit databases can often be tough to put to work, but the CLF’s case was fairly straightforward: They simply searched for company’s addresses in a publicly available database. We would love to hear cases of more groups using this approach or other simple modes of regulatory engagement.

Excerpted and Adapted from Mathew Lippincott with Shannon Dosemagen, The Political Geography of Aerial Imaging, 19-27 Drones and Aerial Observation, New America Foundation 2015.

Sources and Further Reading:

Alsentzer, Guy, Zak Griefen, and Jack Tuholske. 2015. CWA Permitting & Impaired Waterways. Panel session at the Public Interest Environmental Law Conference, University of Oregon.

Conservation Law Foundation Newsletter “Coming Clean”, Winter 2014;

D.C. Denison, “Conservation Law Foundation suing alleged polluters”, Boston Globe, May 10, 2012.

Russell, Karl and Charles Duhigg, Clean Water Act Violations are Neglected at a Cost of Suffering. In The New York Times, Sept 12, 2009. Part of the Toxic Waters Series

Follow related tags:

evidence epa blog water

What goes into choosing a topic name?

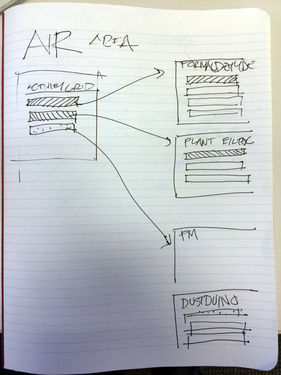

above: sketch of figuring out how to organize "air" into a research area, and which methods are part of the research area, and which activities would go on what grid...Photo by @nshapiro

We've been having some fun discussions over the past couple months with people on each of the topical lists about what to name the new "top-level" pages where we're organizing. That means -- when posting activities, do they end up on /wiki/balloon-mapping or /wiki/aerial-photography? Do we use the older /wiki/spectrometer page, or the new one at /wiki/spectrometry? But we're hoping for even MOAR discussion!

Let's think about:

- where and how these new pages will show up -- most likely on a dropdown menu and maybe eventually on the front page of publiclab.org,

- and, the timing -- we're prioritizing the creation of these "origin" pages amidst all the creation of activities and activity grids we've been working on and will continue to work on through Barnraising.

So far we've created drafts of:

- http://publiclab.org/wiki/spectrometry

- https://publiclab.org/wiki/coqui (created over LEAFFEST weekend; this will, in turn, be linked into a top-level water page once we figure out what to name it)

- https://publiclab.org/wiki/aerial-photography (first draft created September 23)

- https://publiclab.org/wiki/open-air (created Sept 27 by Nick, Leslie, Liz, and only lists the plant-based air filter kit so far)

Up next:

- https://publiclab.org/wiki/multispectral-imaging with @cfastie for all our infrared photography work (actually, it's drafted but needs to be automated.) (Also, that's a really long, and to some, an unrecognizable name.)

- https://publiclab.org/wiki/pole-mapping (possibly, with @ekta64?)

- https://publiclab.org/wiki/open-water (which in turn will link to Riffle)

When naming new pages, some things to consider are that names should be:

- short and usable for tagging or telling someone about

- engaging to existing contributors and long-standing members of our community

- not jargony in a way that it blocks new people from accessing the topic -- think accessibility, but also think about how we can make our topics problem-based, rather than theory-based

- in alignment with terms people are searching for on the internet at large: https://www.google.com/trends/explore?q=aerial%20photography,aerial%20mapping,drone%20photography https://www.google.com/trends/explore?q=infrared%20photography,multispectral%20imagery,ndvi

Looking ahead, we have more naming to do! There are some mismatched names:

- "dssk" vs. "desktop-spectrometry-kit-3-0"

- "infragram" vs. "infrared" vs "multispectral-imaging"

- "timelapse" vs. the broader" photo-monitoring"

We'd really like to hear from a wide selection of voices about naming! Please pile on in the comments! Thank you!

Follow related tags:

blog with:warren with:cfastie with:nshapiro