The Public Lab Blog

stories from the Public Lab community

About the blog | Research | Methods

Remembering Tonawanda

For ten years, community members fought to hold Tonawanda Coke accountable for poisoning the air in Tonawanda NY. Using buckets, summa canisters, and tenacious organizing, they collaborated with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYS DEC) and found that the amount of benzene emitted by Tonawanda Coke was nine times higher than what was being reported to the EPA.

Jackie James Creedon is a founder of the Clean Air Coalition of Western New York (CAC) and Citizen Science Community Resources (CSCR) and a contributor to Public Lab, as well as an advisor on the bucket monitor project. She agreed to share her story, which has been lightly edited with permission.

Toxic in Tonawanda: Unexplained Cancers

What happened in Tonawanda?

Really, what was intended was to clean up our own backyards. I was diagnosed with fibromyalgia. I didn’t know what caused it. In January of 2002 there was a front page Buffalo News article called “Toxic in Tonawanda?” They interviewed a bunch of people, residents and workers in the area who were all sick. It was people’s stories. Not only were they sick, but there were stories of how their animals had strange diseases and ended up dying. I saw the article and that was really the impetus for me to start researching and finding out what was going on.

I said, “Something doesn’t seem right.” So I reached out to some of those people and just started asking a lot of questions.

Buffalo News article, “Toxic in Tonawanda?”

Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

Buffalo News article, “Toxic in Tonawanda?”

Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

There was another factory that rolled uranium for the atomic bomb in Tonawanda, and some of those workers worked for this other factory and they were very ill. There was this feeling that that was what was making everybody sick. The residents and the workers had voiced their opinions pretty loud, so the New York State Department of Health came to investigate. They conducted a cancer surveillance study from 1994-1998. They came to Tonawanda to announce their results in 2002. Sure enough, it showed certain cancers and overall cancers were significantly higher than the state averages. They said that none of the cancers that were elevated were associated with uranium exposure, so they just sort of packed up their bags and went home.

I specifically remember that day, that evening, saying, “If it’s not that, then what is it? I want to find out.”

Toxic Bus Tour and Global Community Monitor

When I started, there was a small local organization called Citizens Environmental Coalition. They had a small Buffalo office with one employee. I reached out and asked them, “Is there a proper citizen’s environmental group in Tonawanda?” And he said “No.” And I said, “OK, I’m going to start one.” The original four of us were Adele, Tim, her husband, and me, and this gentleman who worked for this environmental organization called Mike Schade, who had worked for Lois Gibbs for awhile. So we started a community organization.

In 2003 I was speaking at a rally for Lois Gibbs -- as you know, Love Canal is not far from here either, it was the 25th anniversary and I was asked to speak about the issues in Tonawanda. It was a Toxic Tour, everyone gets on a bus. We were in Tonawanda, I was speaking, that’s when Adele approached me. She said, “You know, I think it’s something in our air that is making us sick.” and I said, “I think maybe you’re right.”

Soon after that I was having coffee with Mike Schade from this environmental organization and he said, “I know of this gentleman in northern CA, his name is Denny Larson, he has this organization called Global Community Monitor. There’s a method to take an air sample called the bucket method.”

What did you originally hope to accomplish?

We wanted to reduce air pollution in our community. None of us were activists, we were concerned citizens, so we had a lot of learning to do. We found out that Tonawanda was home to 54 air regulated facilities. That’s a lot. We also read some brochures about how to get organized and Denny sent us a book about how to run a good neighbor campaign. And that’s what we decided, that we wanted to run a good neighbor campaign based on the results of the bucket.

So from there, Denny had a small grant, he came to Tonawanda, we met in somebody’s basement. Probably 8-10 of us. And we built a couple of buckets. He showed us how to use them. At that point we really only had one bucket. So then we had a bucket, we knew how to use it. And that’s when we learned that we needed to do a brigade.

.

.

Denny Larson with the “Bucket”, 2003. Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

What is a bucket brigade?

A brigade is hunting for a smell. Because these industries pollute mainly in the middle of the night. We had to set an alarm and go out in the middle of the night. So we did that a couple of times. The infamous time that we collected an air sample with our bucket was either the first or the second time. We didn’t do it a lot. The buckets are cheap to make, but it’s expensive for the analysis. You really want to make sure to capture a “bad” smell, because it’s only a three minute sample, and those odors can move really quickly. Apparently we did a good job in capturing it!

At this point we had no idea that most of our polluted air was coming from Tonawanda Coke. We just knew our air stunk. It was August 2004 that we held a bucket brigade at night, we captured an air sample to have it analyzed. We got the results back and still didn’t know what all the numbers meant. We met in Tim’s living room and planned how we were going to announce the results. And that’s when we changed our name from Toxic in Tonawanda to Clean Air Coalition of Western New York.

Building the “Bucket” with Denny Larson, 2003

Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

Building the “Bucket” with Denny Larson, 2003

Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

The Tonawanda Bucket Brigade, 2004

Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

The Tonawanda Bucket Brigade, 2004

Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

Carbon Disulfide and the 3M Campaign

Besides benzene, we also found another chemical called carbon disulfide that we were concerned about. We figured out this was coming from 3M which has a sponge company in Tonawanda.

3M Factory, as seen in Google Maps

3M Factory, as seen in Google Maps

See, Tonawanda was a complicated situation because there were 54 air regulated facilities in a very concentrated area. Tonawanda has the highest concentration of regulated facilities in all of New York State. It was hard to figure out who was doing what. It took a lot of research. So we figured it out, it was carbon disulfide and benzene. Carbon disulfide was easy to figure out, 3M was really the only source. So we met with 3M, trying to do the good neighbor campaign. We met with the owners and we were pretty satisfied. We were working with an engineer at the NYS DEC that we felt we could trust and he went there with us. 3M actually flew someone in from their headquarters to give us a presentation on everything that they’re doing to reduce emissions in Tonawanda. They treated us very respectfully. They met with us, said, “This is what we’re doing,” and guess what? They did it!

So we were like, “OK! This seems pretty easy. Let’s move on to the next one.” Beginner’s luck. Well, then the fun began! So the benzene. We took the sample not far from the expressway, but we didn’t know where it was coming from. We had our monthly meetings at the local fire hall on Saturday mornings, and one Saturday morning this engineer from NYS DEC attended our meeting. He was the one who said, “You might really want to take a look at Tonawanda Coke. The owner is sort of a bad actor.” He was the one that started dropping ideas to us at those Saturday morning meetings that maybe something was up.

Tonawanda Coke, 2018. Image courtesy of Paul Leuchner of Citizen Science Community Resources

Tonawanda Coke, 2018. Image courtesy of Paul Leuchner of Citizen Science Community Resources

Using Summa Canisters to Verify Bucket Results

We were working very closely with DEC at this point. This engineer named Al Carlacci was very respectful to us. He listened to us. We were respectful too. We didn’t demand anything. It was really about relationship building and getting to that point of trusting each other, which is huge. Figuring out who you can trust, who you can’t, who’s going to help you, who’s not going to help you. Anyway, this guy Al was really a good guy, he meant it. So he took our data and said, “Yeah, you know, it’s high, but it’s only one three minute sample.”

So he started his own investigation with the summa canisters. He took the canisters out -- I’m not sure how many samples he took -- and sure enough, replicated what we got in the bucket. Based on what we did, and his results, the NYS DEC applied for an EPA grant for air monitors in Tonawanda. They were awarded a $600,000 EPA grant to place four trailers in our communities to collect air samples and analyze those air samples for one year, from 2007-2008.

NYS DEC Air Monitoring Trailers, 2007

Image courtesy of New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

NYS DEC Air Monitoring Trailers, 2007

Image courtesy of New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

That was a big win for us, to get those air monitors.

Benzene and the Tonawanda Coke Campaign

About six months into their study, we received some preliminary results. Again, at that point, nothing was for sure, but it started to look more and more like the main source of benzene was Tonawanda Coke. In Fall 2008, based on the data and the DEC engineer, and people’s stories, putting everything together, we still sort of felt like we were doing a lot of different things.

Tonawanda Clean Air members meet with Lois Gibbs (second from left, front row),

Jackie James Creedon (center, front row).

Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

Lois Gibb’s (Citizen Health and Environmental Justice) group came into Tonawanda in 2008 to help us get organized. The best advice they gave us was, “There’s not many of you, so it’s best to draw the line in the sand and concentrate on one thing.” After that, we decided that we were going to run a direct campaign against Tonawanda Coke in Fall 2008.

Our first step was to try and meet with the owner of Tonawanda Coke! We sent him a letter and said we wanted to meet. We’ve got this preliminary data, we’ve done the research which showed with the EPA TRI that Tonawanda Coke was one of the highest sources of benzene in our community. We received a letter back from their lawyer saying, “We don’t want to meet with you. We are a good neighbor.”

We asked them three times. The first one was the letter and we were rejected. The second time we decided to hold a forum where we invited J.D. Crane --the owner -- to this community forum and put a chair up on stage with his name on it. We invited everyone from the neighborhood to describe how his pollution was impacting our health. That was a media event, part of the campaign to hold Tonawanda Coke accountable. We started ratcheting up the pressure. In April 2009 the EPA special investigative forces from Denver came in to conduct an investigation. That was really important, because it was based on a lot of the work that we had done and the collaboration with DEC and EPA that spurred this investigation in April 2009. At the same time, Obama had just come into office, and he gave the EPA a lot of authority to investigate these bad actors.

2009 Tonawanda Community Air Study

That was spring of 2009. DEC came to Tonawanda in June 2009 to give their results of that one year study from the air monitors. What they had announced was the smoking gun. That data, that study was the smoking gun that we all needed. Between us starting the direct campaign in 2008 and the EPA coming to Tonawanda and then the DEC announcing the results in June 2009, the pressure was really mounting. At the June 2009 meeting, the officials announced that hazardous air pollutants, HAPs, in Tonawanda were elevated and needed to be reduced, and the most concerning was benzene.

They took these four air monitors and triangulated what direction the benzene was coming from based on wind roses. This one slide was perfect, it triangulated and in the middle of the triangle was Tonawanda Coke with a circle around it. “The predominant source was Tonawanda Coke.”

Benzene pollution roses, image courtesy of New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

Benzene pollution roses, image courtesy of New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

At that point, I remember in the auditorium standing up and clapping, because here I am, a scientist thinking, “This is it!” It’s all over and done with. Here’s the science, it’s gotta be enough. I was wrong, it wasn’t enough. After that I thought the EPA and DEC would come in and start doing stuff right away, but they didn’t. It was really frustrating. We knew we were in a gas chamber and they weren’t doing anything about it.

At the same time, I was getting tired with fibromyalgia again. We were making huge strides, but it was exhausting. I knew that we needed a good push to get the agencies to act on the situation. So we decided to hire a community organizer that had experience with organizing, more than what we had. In September 2009, I stepped down as Executive Director of the Clean Air Coalition and we hired a young experienced organizer. We had asked J.D. Crane to meet with us three times, and three times we had been rejected. We knew we needed to hold a protest outside the gates of Tonawanda Coke. That was our new Executive Director’s first directive from the board.

Tonawanda’s Clean Air members hold a protest outside the gates of Tonawanda Coke, October 2009

Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

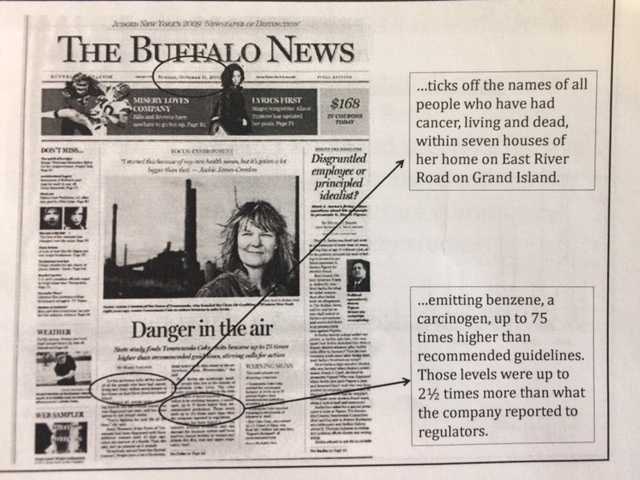

We held the protest and we got phenomenal coverage. We were on the front page of the Buffalo News, huge article. Tons of press. This was exactly what we needed, because it got the attention of the Department of Justice. Aaron Mango, a resident of Buffalo, is a prosecuting attorney for the Department of Justice for the Western New York region. He just happened to go to his parent’s house that Sunday and saw the paper on the kitchen table. It caught his eyes right away. He read the whole thing.

The two things he said stood out to him were the people’s stories and the data, the statistics, when the New York State Department of Health came in and there were all the cancers.

Buffalo News article that caught Aaron Mango’s attention, October 11, 2009. Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

So here you have cancers you know are high, and you have people’s stories, the complaints. The next day, he wrote an email to Washington DC and said, “I want to investigate this company, something doesn’t seem right.”

We had a multiprong campaign approach. Not only did we have New York State DEC and EPA coming at them from the civil side, but then the Department of Justice came in on a federal investigation, which was huge. When the federal government starts to investigate, they don’t tell you much. We didn’t even know Aaron Mango saw this. The next thing we knew, two days before Christmas in 2009, the DEC, the EPA, the federal agents -- the US Coast Guard -- raided Tonawanda Coke and took out the environmental manager in handcuffs. They arrested him. We had no idea that was coming. 2009 was a good year, we really accomplished a lot. But there was a lot of work that led up to these victories.

How did DEC and EPA find out about the bucket samples?

It was the DEC engineer, Al Carlacci. He got involved because he really cared. It wasn’t his facility, but he was helping us out.

Larry Sitzman and one or two engineers who worked with Al had done the inspections of Tonawanda Coke, and they were turning their heads. I heard stories about envelopes being exchanged to look the other way. DEC was criticized for letting this go on for a very long time. We didn’t know how bad it was until we saw the photographs, when the DOJ went in, they took all these photographs. It was absolutely horrendous. How could someone turn their head on this?

A coal tar moat under dilapidated piping at Tonawanda Coke, 2018

Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

A coal tar moat under dilapidated piping at Tonawanda Coke, 2018

Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

But they did. Al Carlacci, he was our champion. You can have an organization with good guys and bad guys in the same organization. People said to us, “New York State DEC, you can’t trust them.” It wasn’t necessarily true. You’ve got to weed out who you can trust and who you can’t. It’s about building that trust, those relationships with people that have information and or power that you can rely on.

You didn’t solicit the lawsuit?

No, not at all. It was mainly science, citizen science, or community science. And then we learned how to organize. Later on came the lawsuits.

That’s an incredible chain of events.

It started with the bucket, then Al Carlacci did his test, which confirmed the bucket, and then the large study confirmed the previous two small studies with more information about where the benzene was coming. That data was huge. It was absolutely huge, the Department of Justice investigations, and the EPA when they came in in April 2009. That was 2010, we started in 2002.

.

CSCR members outside the shuttered Tonawanda Coke, October 2019

Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

.

CSCR members outside the shuttered Tonawanda Coke, October 2019

Image courtesy of Citizen Science Community Resources

2010-2016: DOJ Lawsuit against Tonawanda Coke

Everything moves very slowly. What would happen is that we would take breaks, we would get tired out. We would come back to it. For me personally, there was always something that drew me back. So many times, I said that’s it, no more, because it was so much work. And I would always come back. But those breaks were really important, because it’s tiring work. A lot of people are really gung ho in the beginning, and then they peter out and they really do give up. These companies and these agencies, they bet on the people who give up, because it’s like a David and Goliath thing. It really is about running a marathon.

What happened after the lawsuits were initiated?

There were two parallel tracks. Since the DOJ got involved, it put a thorn EPA’s side to get the civil enforcements going. We had federal and civil actions, and on top of it we had personal lawsuits that came soon after. It was sort of complicated. It really initiated the EPA to get their act going and hammer down on Tonawanda Coke. They had negotiated with the owner to reduce their emissions. But before that, EPA ordered Tonawanda Coke to hire an independent third party engineering firm to measure the amount of benzene that was actually coming off the company using something called DIAL testing, differential absorption light detection. The EPA and DEC had data from the air monitors in Tonawanda, but they didn’t have stack and process monitoring data from Tonawanda Coke.

These companies self-report, which is another horrible situation. As residents, we are relying on these companies that pollute to tell the truth. Well, generally speaking they don’t tell the truth. Not only was Tonawanda Coke not telling the truth, they were really not telling the truth. When EPA came in with DIAL testing, they discovered that Tonawanda Coke was grossly underreporting their benzene emissions. TCC was reporting that they were emitting ten tons of benzene per year, when in actuality they were emitting 91 tons per year. When I saw that, I was like, “We are living in a gas chamber. This is horrible.”

Obstruction of justice and the pressure release valve.

At state or federal permitted facilities, there may be multiple sources of pollution (into the air, soil, and/or water) coming from one company. Each emission source requires a permit. There were a couple of air permitted sources at Tonawanda Coke. However, there was something that seemed to be amiss because the discharge numbers weren’t adding up correctly. Al Carlacci and the DOJ figured out that there had to be another source of benzene pollution that TCC was not telling them about. Sure enough they were right! There was an emission source called a pressure release valve. TCC was emitting tons and tons of benzene and coke oven gas, and it was mostly coming from this unregulated valve. This all came out in the federal case against Tonawanda Coke.

In March 2013, there was a trial. When the federal government comes after you -- there were 15 indictments, mainly violations of the Clean Air Act -- you settle out of court because you know chances are you’re gonna lose. Well, Tonawanda Coke did not settle. They fought us. And then they fought everybody: the DEC, the EPA, and the DOJ. There was a trial and all this information came out in the trial. It was very interesting. What we found out in the trial was that there was this pressure release valve.

We also found out that employees were directed to conceal and hide that pressure release valve. And that is why the environmental manager went to jail. He was found guilty of obstruction of justice. When the EPA investigators came in, lo and behold, guess what happened? The pressure release valve went off. That was unbelievable. The inspector said, “What’s that?” and the employee said, “Oh, it’s just steam.” Well guess what? It wasn’t just steam. The agencies and DOJ suspected that most of this benzene -- this 91 tons of benzene -- was coming from this unregulated air source, and Tonawanda Coke tried to conceal it!

Sentencing Phase: Benzene Reductions and a Legal Mandate for Soil Testing

Tonawanda Coke and their environmental manager were found guilty in March of 2013. There was a year in between the guilty verdict and sentencing, March 2014. At that point I thought, “Oh great! That’s the end! We won!” The DOJ, the special investigator that we were working with said, “Jackie, if you have a guilty verdict, we’re only halfway there. We need a good sentence.” Judge Skretny requested that the community send in their stories. We rallied the community to send in their stories and weigh in on the sentencing of Tonawanda Coke and the environmental manager. The judge also wanted the community to submit project proposals for possible funding at the sentencing of Tonawanda Coke.

At this point we were testing residents’ soil. Once again (as with the benzene pollution), this testing started because of people’s stories. Folks were complaining about these black gooey substances flying through the air and burning holes in people’s vegetable plants, and in the paint on their cars. So we started doing soil testing and sure enough, we found contamination in the soil. We took that data and put it into a $700K project proposal and submitted it to the judge.

It all came down to one day in March of 2014, this one person, Judge Skretny, deciding the fate of Tonawanda Coke and the environmental manager. Was the community going to get anything? This case was historical in a lot of ways. It was only the second time in history that a company was convicted under the Clean Air Act in a federal lawsuit, and it was the first time that a judge ordered community projects as a term of probation at sentencing. At the sentencing, TCC was ordered to pay $12.5 million in fines and $12.2 million in community studies. So he funded the community, and our $700,000 soil study!

This was the beginning of Citizen Science Community Resources.

That was huge! We were not even a non-profit. He also funded an $11 million University of Buffalo health study. The environmental manager was sentenced to a year in jail. He was fined $20,000. It was obviously a big win for our community. And on the civil side, Tonawanda Coke agreed to install pollution control equipment. Their benzene was reduced by 86 percent in our community. We got our reduction in benzene. TCC didn't fight the civil actions, they settled that case. There was also $1.3 million set aside for community projects. In total, the community got over $13 million for environment and health projects..

In the same year, J.D. Crane, the owner of TCC, had passed away. He was 92 years old. His grandson, Paul Saffrin, took over the business. Mr. Saffrin vowed that he was going to turn everything around and be a good neighbor. We thought as a community, “OK, we got our benzene reductions, we got our community projects, let’s give this guy a chance.” But over the next several years, nothing really had changed.

This facility was a 100 year old facility. Just the nature of such an old dilapidated factory, there were things that were polluting our community, and people were still dying. OSHA wound up going in. There was this incident where the safety control on a conveyor belt wasn’t put into place and a gentleman’s zipper on his jacket got caught. Poor guy got pulled in and died! Things like this kept happening. Another time, there was an explosion. People got hurt. We would hear stories about something happening consistently. TCC employees were leaking information to community members, and then other community members were calling me. The DEC would get an inclination that something happened, and they would follow up. Tonawanda Coke would give them a bullshit story. Some employees with Tonawanda Coke were talking with people from the community and calling me with the real story, and then I was going back to the DEC. Again and again and again, there were these upsets. They’d lie about it. They’d get caught again. It was continuous.

July 2018: StoptheStacks and the closure of Tonawanda Coke

The final upset happened in January 2018. There was an underground tunnel that collapsed. We started seeing black billowing smoke coming out of the facility again. TCC was giving us bullshit again, “It will be fixed, it will be fixed.” Everyone started taking photographs and putting them on social media. At this point, TCC was still under probation with the DOJ and the DEC was on their butt too. Everyone was so sick of this company. The amount of energy that went into trying to keep these guys following environmental rules and regulations was enormous. It was ridiculous.

There was a huge fire in July of 2018. The fire trucks came to Tonawanda Coke. We started getting all these complaints and people taking photographs from the expressway. A few TCC employees drove a forklift to the entrance of Tonawanda Coke and wouldn’t let the fire company in. They told them, “Go away, we’ve got it handled.” TCC was such a bad actor. That’s when we ran the campaign, StoptheStacks.

At this point, the community, elected officials and the agencies had had enough. We gave them another shot, but they blew it. We decided, “We want them gone.” Our local official, Town of Tonawanda Supervisor Joe Emminger and the town board all went on record saying, “This company needs to go.” That was huge, because they had had enough too. “The amount of taxes we are getting from this company are nothing compared to the people who are being put into harm’s way, the workers who were put into harm’s way, the pollution, the stress. “ So that was it. A multipronged approach with everyone rounding the wagons against Tonawanda Coke.

In October of 2018 Tonawanda Coke announced that they were closing their doors and shuttering the plant. That’s the end! We have clean air now in Tonawanda. Our cancer risk due to benzene, at one point, was 75 times New York State guidelines. Now it’s down to New York State averages. We also have a significant reduction in particulate matter and many other toxins. All those other companies, when they heard and saw what the community had done, they really got their act together and installed more air pollution equipment. It was a domino effect. We were to be taken seriously.

Image courtesy of New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

It wasn’t like that at the beginning. At the beginning we didn’t even go to our elected officials because very few wanted to be on our side.. But it was the data, and working with NYS DEC and EPA. When we had that solid data from the NYS DEC “Tonawanda Community Air Quality Study”, that’s when everything turned around.

Remembering Tonawanda

In March 2014, Tonawanda Coke was fined $12.5 million and ordered to pay $12.2 million in community service projects by the U.S. Department of Justice after the company was indicted and convicted of breaking federal criminal and environmental laws the previous year. It was only the second time in history that a federal criminal case had been successfully tried under the Clean Air Act and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). In subsequent civil proceedings, the company settled a suit with the State of New York and the EPA by signing a consent decree and paid $2.75 million in civil penalties for violations of the Clean Air Act (CAA), the Clean Water Act (CWA), and the Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act (EPCRA). Additionally, the company spent approximately $7.9 million to reduce air pollution and enhance air and water quality, and $1.3 million for environmental projects in the area of Tonawanda, New York.

What was your journey like? How did you build knowledge over the course of this campaign?

My background is science. Science always intrigued me. I like to ask a lot of questions, put it all together, and try and figure things out. I think that the biggest knowledge that I personally gained was this: I thought once we had this data, that that would bring us a victory. I was wrong. It was a significant pivotal moment in the story; however, it wasn’t enough. I’ve heard from other communities who use citizen or community science, that they struggle with same thing. The science is not enough. It’s about taking that science, and learning how to use it to advocate for your community. A big part of winning is about relationship building.

Do you think this project would have been different if DEC had not done the follow up study?

I think Tonawanda Coke would still be operating today. I had a resident call me the other day and say thank you. It had dawned on him, because of this COVID-19 situation, how it impacts people’s lungs. That’s how their coke oven gas was impacting our community. It’s benzene, but it’s also black soot, particulate matter. He said, “Oh my gosh, if TCC’s air emissions hadn't been eliminated, we would be much more sick with COVID.” We really saved lives. However, there were a lot of lives that were lost. It tore my heart out so many times. People who had cancer that we lost. They knew in their heart what had caused their cancer and wanted to do something about it for the short period of time they had left.

Why did you decide to change the name?

In 2003, when we started we called ourselves Toxic in Tonawanda. But after we collected the first set of data, we thought that name was a little too radical. We wanted to seem credible. That’s when we changed our name. The original group was the Clean Air Coalition of Western New York, now we’re Citizen Science Community Resources.

What do you remember most vividly about doing this work?

It’s taken a long time for me to digest everything. That all of this happened.. It’s important for me to tell the story because I remember how important it is to pass along the lessons learned. Much of our society operates by putting profits and power ahead of the environment and people's health. I didn't know this before. It was a sad reality for me. TCC polluted our community because they thought they were above the law. All at the expense of our health and our environment. We need to change our systems where we give more significance to saving people's lives and health and safety of our communities.

What would you recommend to others who are just starting a campaign like this?

I remember Denny talking about this. Usually fighting lean and mean is a good idea. It’s really important to be careful about who you bring into the fold, into the core group, and to be able to rely on those people. There were many times when I took the lead, or Tim took the lead, or Adele took the lead. We sort of cycled. But the four of us -- mainly the three of us -- we were all on the same wavelength. The environment and health of our community always came first.

These small meetings with the state agencies were so important. Don’t bring the issue up in the media right away, then you lose all sorts of trust. Media should be used right at the end as a last ditch effort. We went to the agencies first and built a working relationship with the people we could trust. There’s certain parts of the story that I feel are really important -- this, for instance, was really critical in why we were successful.

And it’s about community science. That’s what it was! Community science.

This post is part of the Bucket Monitor project.

For more information, see our introduction and project overview.

Subscribe to the tag "bucket-monitor" to get updates when we post new material.

Subscribe to get updates on this project

Follow related tags:

epa air-quality history blog

Black Lives Matter.

Note: this statement was previously shared in our monthly newsletter

Black Lives Matter. Public Lab stands with the millions around the world who have raised their voices in protest of police brutality and systemic injustices toward Black lives. Further, from the expansion of oil and gas facilities in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, to the chronic inaction toward the effects of climate, and the systematic targeting of polluting industries towards BIPOC communities — all stem from a legacy that is rooted in and perpetuated by oppression, racism, and violence.

We commit to supporting Black voices, movements, and organizations. We commit to centering those that have historically been (and continue to be) excluded from science, technology, and environmental decision-making. We commit to maintaining a welcoming community, free from racism, with accessible places of entry into community science that elevate, build, and strengthen the capacities of communities and their leaders to rise. And we commit to dedicating our resources to forefronting leadership from those disproportionately affected by environmental injustices and systemic racism.

Public Lab recognizes and honors the lived experiences and expertise, and strives to build relationships grounded in trust with frontline communities. We envision a future where those most impacted by environmental injustices direct the efforts to protect their communities, collective health, and well-being.

Follow related tags:

blog

The Bucket: Updating and open-sourcing a community air monitoring tool

By: Dr. Gwen Ottinger (Fair Tech Collective) and Shannon Dosemagen

The "bucket" is a low-cost, community-friendly air sampler that helps people measure toxic chemicals such as benzene and hydrogen sulfide in their air. Developed in the late 1990s, it was one of the first (if not the very first) do-it-together environmental monitors. Communities living next to oil refineries and petrochemical plants gathered to build their own buckets. They established phone trees to make sure that, when noxious fumes enveloped their neighborhood, someone would take a sample. They used measurements from the samples to hold companies accountable, not only for their emissions but for lying to communities about them.

The buckets were a source of inspiration for each of us, early in our careers. Gwen saw them as a powerful new way that communities could participate in science and challenge the shortcomings of scientists' approaches to understanding pollution. They led her to her dissertation research and inform the conclusions of the book she is currently writing about the role of science in restorative justice. Throughout Shannon's early career, she focused on creating collaborative spaces by connecting people to their local environment using science, art, and media. Attracted to working with the Louisiana Bucket Brigade because of the direct link the organizing model made between science, data, and advocacy, Shannon went on to co-found Public Lab. Her hope was that, in a time of rapid technological innovation, Public Lab could be a vehicle to build on and expand the science and advocacy model into other realms of addressing environmental injustices.

Revisiting the bucket in 2020

Over the past decade, buckets have fallen out of favor. Communities have become more focused on particulate matter, which buckets don't measure, even though toxic chemicals are still a problem. They seek continuous measurements of air pollution, rather than the snapshots of just the worst moments. Regulators are increasingly willing to support community monitoring, but homemade technology has seldom been incorporated into these projects.

All of these trends in air monitoring have their benefits. But the buckets have singular advantages. They are hands-on and highly visible. Their results are easily linked to concrete demands for change. They let people take action in the moments when they may feel the most powerless. They remain an important part of the community monitoring toolkit.

While buckets are still important, the infrastructure for supporting communities in building, deploying, and organizing around them is eroding. The organization Global Community Monitor was a hub for bucket-related resources and expertise, as well as the institutional memory of the bucket brigade movement. Its dissolution in 2016 left a hole that can only partially be filled by regional organizations.

We want to make sure that environmental justice communities continue to have the ability to measure toxic chemicals (as well as particulate matter). With support from the 11th Hour Project, we've launched a project to update and open-source the plans for buckets, to identify best practices for incorporating them into community campaigns, and to create a blueprint for an infrastructure to offer support and mentorship to people who want to use buckets.

We extend deep appreciation to groups such as Global Community Monitor, Louisiana Bucket Brigade, Communities for a Better Environment, and the self-organizing and regional bucket brigades around the world, for decades of work building buckets, refining their design, and developing a model for integrating buckets into organizing. We will be building on their work within the infrastructure of Public Lab. That will mean using wiki-based collaborative editing, individual research notes, a question and answer system, and activities, to comprehensively document the bucket tool, the ways in which it can be used, and steps for getting people started. We'll also leverage the social network of Public Lab, which links technologists, scientists, educators, and organizers together to integrate tools like this into strong, collaborative systems that support the efforts of communities impacted by industry.

Through the end of 2020, you can expect to see:

- An updated and digitized bucket manual: We will be creating a version of the bucket manual that can be easily accessed online, as well as a run of hard copies for distribution. The updated manual will include information and illustrations on building the sampling tool.

- An open-source bucket design and availability of bucket parts: We will be creating a series of activities and notes that describe both the technical setup and steps for how you can use the bucket to support action-based outcomes.

- A blueprint for infrastructure supporting a distributed community of trainers: We will identify the landscape of bucket brigades and suggest a framing for a distributed support network. Part of this process will include identifying potential lab partners willing to do air sample analysis of bucket samples.

We encourage everyone to follow along and get involved by subscribing to the "bucket-monitor" tag on Public Lab.

Follow related tags:

air-quality blog bucket-brigade oil-and-gas

Announcing MapKnitter 3.0

Over the past year we’ve been working hard on a new system for exporting maps in MapKnitter, and have been beta testing the new “Cloud Exporter” for the past several weeks.

Today we’re shutting down the old exporting system as a part of the full launch of MapKnitter 3.0, and I wanted to offer a little background on this transition.

Exporting

What is exporting in MapKnitter? Basically, when you upload a bunch of aerial photos -- from a balloon mapping trip, for example -- you have just a collection of images on a map. It’s interactive, and it’s great for viewing online, but there are a variety of reasons you might want to download a single, high resolution combined image of your entire map:

- to print it out

- to use it in a GIS program

- to archive it

- to email it or embed it in a PDF

Folks have been used to being able to download a copy of their map in this way, in JPG, GeoTIFF, or even TMS format. But it hasn’t been easy!

This exporting process can often take HOURS, because it involves processing GIGANTIC images -- it’s not unusual to see a 20,000x20,000 pixel image result from a big map! This was all running on our server, and any time you’ve seen slowness on MapKnitter.org, it’s likely that the website was in the middle of a major export. It’s not a great way to run a website, and it was pretty expensive as well.

Cloud exporting

What we’ve done is to create a cloud-based exporting service that’s completely separate from MapKnitter.org, and to which we submit jobs, almost like a printer. That means there is no effect on the website speed, and theoretically, you can submit as many jobs as you like, and our system can scale up to handle them. It’s still not free, so please go easy (or consider donating to support our work!) -- but it is pay-as-you-go, so we’re not always paying for a massive server to be online all the time in case someone runs an export. We also incorporated a lot of other improvements. So, what’s changed?

What are the differences?

- New: each export is now archived in a list, rather than overwriting previous exports

- New: you must select images in order to export, so you can export different parts of your map individually

- New: exports run only on selected images, not all images

- New: where to find the “start export” button (it appears in the upper left once you’ve selected images)

- New: you can run multiple exports at the same time

What is the same?

- Same: all previous formats are still exported: JPG, GeoTIFF, TMS, ZIP

- Same: closing the page will not stop the export

- Same: privacy (or lack thereof) in anonymous maps was not altered in this release

This release coincides with a LOT of other changes across the entire MapKnitter.org website, many of which came out of last summer’s Google Summer of Code program, and the Google Community Atlas grant we received in 2018-19. These include:

- Separation of the "view map" page from the "edit map" page, i.e. https://mapknitter.org/maps/kinneil-roman-fortlet vs. https://mapknitter.org/maps/kinneil-roman-fortlet/edit

- Group selection of images

- An interactive tour of maps around the world at https://mapknitter.org/

- "Nearby maps" listings on each map page

And literally thousands of other changes and refinements, many “under the hood” that you may never notice, but which have been critical to updating the MapKnitter codebase to 2020 and ensuring it is maintainable, sustainable, and reliable for years to come.

Thanks to EVERYONE who helped to make this happen!

You can read more about the exporter on this page: https://publiclab.org/wiki/mapknitter-cloud-exporter

Follow related tags:

balloon-mapping kite-mapping mapknitter software

Celebrating our tenth anniversary

In the first weeks after the BP oil disaster — what would become the largest oil spill in U.S. history — concerned residents came together with weather balloons, rigged with digital cameras, to document the extent of the damage to the beaches and wetlands, fisheries and wildlife. Photos and the resulting maps we created with our “community satellites” showed the damage and the scale of the disaster, and would go on to be shared with media around the world.

In the wake of the spill, we began to question how we could use this success as a model to help redistribute power, by making science something that anyone could access — where people with different forms of expertise are recognized for the value of lived experience and local know-how. We envisioned a network in which people down the block or on the other side of the world could work together on solutions, learning from each other’s experiences. It was through these ideals that Public Lab and our community science movement were born.

We're committed to building a healthier and more equitable world, and we're proud of the work we've accomplished in the past decade with our diverse network of partners and friends around the globe. Throughout the year, we'll be sharing stories from some of these community members on this special anniversary page — a look back at the work we've done together, and a look forward to the many tasks ahead. We encourage you to share your own Public Lab memories with us on social media using the hashtag #PL10.

To support and recognize the incredible work that has been accomplished by the community, please consider making a monthly gift of $10. Your contribution will support the infrastructure, partnerships, and movement building that make community science a valuable tool for those most impacted by environmental pollution.

Thank you to Yutsi for commemorative artwork celebrating Public Lab's anniversary. Check out more on their Twitter and Instagram.

Thank you to Yutsi for commemorative artwork celebrating Public Lab's anniversary. Check out more on their Twitter and Instagram.

Follow related tags:

blog anniversary pl10

A note on my departure

Dear friends,

As Public Lab enters our tenth year, I will be leaving my role as Executive Director to pursue my own next steps, with the goal of making room for new leadership and growth amongst our dynamic nonprofit team. I have high hopes for how Public Lab will transition into our second decade, bringing new ideas and opportunities for the community.

Transitioning out at this moment, with the uncertainty of COVID-19 around us, is not easy, but I'm happy to share that during the transition period, Stevie Lewis, our senior program director who has been a core member of our staff for the last six years, will be acting as interim executive director. Through December 2020, I will be staying on as an organization advisor to support Public Lab through the transition period. The hiring committee to fill my position is being led by board member Mike Ma, and we expect to have identified a new executive director by fall 2020.

Looking back to April 2010, I'll never forget the initial moments of the BP oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico or the collaborative spirit in which we all came together to figure out solutions to document the impact. It is this spirit that has driven our collective work and led to some of the greatest collaborations I've ever experienced. In those ten years, we saw the possibility to employ technological infrastructure, scaling the ability of people to collaborate on environmental problems with others in ways that hadn't been done before. I experienced collaborations with hundreds of people around the world working on addressing topics such as mining, oil extraction, water quality, and wetland health. I also witnessed the growth of the community science movement, which has amplified the ability for people to use science to advocate on behalf of the places they care about. Over the past decade, our nonprofit budget has grown from several thousand dollars to over one million, supporting the infrastructure, staff, and partnerships that make our collective work possible. All of this happened because of the community, and I'm grateful to you all for working to create our reality.

I am departing my position (but not the community!) with Public Lab at a point where we've never been stronger, and for this I'm truly happy. With a clearly articulated vision and strategy, incredible staff, a strong community, and a supportive board of directors, I know we're well set-up to take Public Lab into the next ten years. The Executive Director position will be posted in the next several weeks. If you or someone you know has the passion, dedication, and experience to take Public Lab into the next decade, we'd love to hear from you. More on this soon.

For now, it's been a pleasure to serve this community. I'm thankful for the amazing journey we've gone on together, and the opportunity to learn and grow with all of you! I'm here for the movement we've built, our collective drive to see a healthier future, and looking forward to watching Public Lab, our partners, and collaborators thrive and grow.

Shannon

P.S. It's April 2020 and that means it's Public Lab's 10th anniversary! Please consider supporting our work as we celebrate a decade and look forward to the future.

Follow related tags:

blog