Evidence project Blog

Slidedeck for environmental lawyers

Here is a basic Public Lab deck with messaging tuned towards presenting to environmental lawyers.

To make it cute, i created a couple of Award Categories for community-collected data, which gave me the excuse to use "trophy" emojis:

Next steps:

- Please re-use this deck to engage more environmental lawyers in our community!

- I'm interested in feedback to make this better and more comprehensive, so please comment!

Other good links to environmental law related topics on publiclab.org:

- https://publiclab.org/wiki/openhour-archive#June+6th:+Exploring+Proof

- https://publiclab.org/tag/evidence-project -- all the content tagged

evidence-projectis great.

Follow related tags:

evidence presentation legal evidence-project

Part 2: ‘Common Legal Issues when using Community Sourced Data’

This is part of Public Lab's 'Environmental Evidence' blog series - an examination of the ways in which the law and the legal system are helpful and harmful - for communities and advocacy groups seeking to use community-sourced data to activate change. 'The Law' can be an incredibly powerful tool for holding polluters accountable, but it is often overly complex, costly, and slow to respond to changing circumstances.

In this three-part blog, Part 1 looked at how the system currently works. This Part 2 will discuss common hurdles in using community-sourced data, and Part 3 will focus on emerging trends, as well as ways in which community and advocacy groups can help shape the discussion of who gets to participate in the scientific process.

Part Two: Why it Doesn't Always Work

In creating the Code of Hammurabi (one of the oldest examples of a comprehensive legal system), King Hammurabi boldly proclaimed that his Code would help "destroy the wicked and the evil-doers; so that the strong should not harm the weak."[1] Alas, it contains almost no references to regulations for government officials or penalties for misbehavior.[2]

This section goes through the three steps used in Part One (identification of a problem, collecting and analyzing data about that problem, and using that data to fix the problem), and identifies common legal obstacles faced by community scientists.

Step One: Identifying the Problem

Sometimes pollution will be obvious; sewage in a stream or black smoke from a building. But it is also often invisible, and the connection between the symptom and the cause often unclear (or purposefully hidden). Without sufficient resources, it can be difficult to spot the problem or know how to measure it. To continue with the community activists v. polluter started in Part One: maybe Shady Business LLC didn't dump its waste from a clearly visible pipeline, but dumped it instead within their property, where the pollution took months to seep into the groundwater and affect the drinking water supply.

Step Two: Gathering the Evidence

In our adversarial system, there is an ongoing tug-of-war between those who seek more transparency and increased accountability, and those who favor the status quo (especially if it benefits them). The same is true in the field of environmental activism, where a step forward (say, in the development of affordable and easy-to-use data collection tools) is often met with some form of pushback.

One such example is the 2015 passage of Wyoming's SF0012/2015 and SF0080/2015.[3] SF0012 makes it legal to imprison people for up to one year if they trespass onto 'open land' but only if they are doing so with the intent of collecting resource data. It also prohibits government agencies from using that data[4] SF0080 expands the definition of 'data collection' to include photographs of the property (regardless of whether someone is physically on the property).

This legislation, spurred by complaints from the cattle industry of meddling by environmental activist groups, is currently being challenged in court by a coalition of environmental organizations.[5] Whether or not the plaintiffs succeed, or the law is changed, it is representative of how the legal system can (legally) impede gathering necessary environmental data.

Even without explicit legal barriers, gathering environmental evidence can be challenging. If attempting to gather evidence to appeal directly to an enforcement authority, specific methods must be followed, including ensuring the integrity of the sample post-collection. That said, many sample collection methods are straight-forward and are detailed in Standard Operating Procedures available online (such as are available at https://www.epa.gov/measurements/collection-methods). Sample analysis is typically more difficult, costly, and requires access to and mastery of instrumentation. Commercial, academic, and government labs can be resources to analyze samples, and if you've communicated with them about exactly how to collect and store your samples prior to analysis, having samples processed in a certified lab can be an excellent way to obtain high-quality data.

Step Three: Turning Evidence Into Action

Can you prove it? Can I trust you? And why should I trust you more than the other guy?

Being able to prove the credibility of your evidence and demonstrate causal relationships are cornerstones of the scientific process. For differing reasons, however, credibility and causation have become increasingly burdensome and difficult for those seeking to address environmental problems. This burden is especially acute in the legal system, where government agencies are given wide discretion in justifying a decision to take/not take action, and much environmental litigation places the burden of proof on the plaintiff, not the alleged polluter.

When it comes to demonstrating credibility, new methods of collecting data and evidence from traditionally disempowered communities or groups face an uphill battle in a legal system where change can be slow and institutional preferences ingrained. And in certain contexts, e.g. litigation, if data cannot meet certain accepted standards, it may not be allowed to be introduced as evidence at all.

Demonstrating 'causation' is especially problematic in environmental contexts. Because cause and effect within ecosystems can be complex and nonlinear, 'proving' x caused y may sometimes be impossible, which is then often politicized to prevent action (the fact that there is still a climate change 'debate' in the U.S. b is a perfect example. In legal contexts, the burden is usually on the plaintiff to 'prove' x within a certain degree of certainty. If you have video of someone trying to barter baby alligators for a six-pack of beer, 'proof' is easy.[6] If you're trying to show an offshore oil spill is affecting inland health, it's not.

The chart below looks at how issues of credibility and causation affect the chance of success in environmental legal actions.

| Type of Action & Characteristics | Pre: Agency Decision-Making | Post: Petitioning for Judicial Review | Citizen Suits & Litigating with Legislation | Public Nuisance | Toxic Torts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How to Initiate | Pre: during public comment period | Post: depends on statute of limitations, but usually one must file claim within appx 3 months | File notice of intent to sue and serve on required parties | File lawsuit in civil court (usually state) | File lawsuit in court (state or federal) |

| Parties | Individual Commenters State/Federal Agencies | Plaintiff Alleged Polluter | State Environmental Agency | Plaintiff Alleged Polluter | Plaintiffs (Class Action) Alleged Polluter Insurance Companies |

| To Succeed, Plaintiff Must: | Pre: be the loudest set of voices (i.e. political value) and present sufficient evidence | Post: show that the in/action was "arbitrary & capricious" (i.e. there can be no reasonable explanation for it, or it was totally beyond the agency's jurisdiction) | Need to make sure that the applicable legislation authorizes citizen suits (or other means to challenge action) | Prove that the action is "a substantial and unreasonable interference with rights common to the general public" That state/federal legislation has not already addressed the issue | Show that they have suffered injury, that the defendant caused it, and that the court has some means to 'fix' or redress the problem |

| Legal Standards for Evidence | Pre: agency must consider all comments, but has discretion over how to weigh them | Post: usually not allowed to introduce new evidence at this point | Varies by state and by authorizing legislation; agency also has a certain amount of discretion in deciding whether or not to pursue action | The relevant state rules governing evidence Case Law (i.e. legal precedent) | Federal Rules of Evidence 401, 701, 702, 703 |

| Duration (these are only very rough estimates!) | Pre: depends on agency, from 1-12 months | Post: depends on specific state/federal statutes (usually 1-6 months) | Anywhere from 2 months to 1+ years | Usually less than 1 year | Years |

| Cost (these are only very rough estimates!) | Pre: no cost -- low cost | Post: if suing agency for its action: cost of hiring attorney and filing motions | If agency decides to pursue: limited cost for individual plaintiff If agency decides not to assist: $ thousands | Main cost is usually cost of attorney and cost of presenting evidence | Some cases are on a contingency basis, but can go into the $ millions |

| Common Problems (faced by plaintiffs seeking to use community sourced data and environmental legal action generally) | Transparency, Wide agency discretion, Limited window for challenging action Pre: Agencies are given a lot of discretion, and agencies are often skeptical towards new or emerging technology / means of collecting evidence | Post: courts will usually give significant deference to the agency's reasons for action / not acting A narrow timeframe for challenging action |

Cost, Participation is Limited by Legislation If the responsible state environmental agency decides not to act; the plaintiff / community must finance Not all environmental legislation has citizen suit provisions It has become increasingly difficult to prove ‘standing’ (i.e. that the plaintiffs have been |

Vague legal standards; possibility of state/federal preemption ‘Nuisance’ has been inconsistently defined For complex environmental issues, it can be tricky to prove causation and ‘particularized harm’ |

Cost, Causation, requirement that courts ‘balance’ the evidence “Battle of the Experts” (such cases can often turn on which side can hire more experts and submit more data Costs can be prohibitive Proving liability and intent can be very difficult, especially when dealing with corporations |

Agency Decision-Making / Petitioning for Judicial Review

In its "Exploratory Study on Barriers," the Wilsons Commons Lab (a non-partisan research institute) identified key obstacles preventing a wider acceptance of citizen science. One of the study's main (and probably unsurprising) findings was that "personnel in multiple agencies have noted a general skepticism of the scientific community toward data collected in this comparatively uncontrolled way, as it is unfamiliar."[7]

Agencies tend to place far more weight on 'traditional' science or evidence (or lack thereof) provided by universities, research institutions, etc., and are not (usually) obligated to explain what specific information they relied on when coming to a decision. This lack of transparency makes it difficult to influence ingrained agency positions or engage in open dialogue.

After an agency makes a decision or takes an action, individuals or group can seek to challenge that decision. While the specific rules vary by state/municipality, courts are (usually) obligated to apply legal standards that are difficult for the plaintiff to meet. The rules (usually) require a plaintiff to show that a) the decision was "arbitrary and capricious" (i.e. totally unreasonable) b) clearly beyond the bounds of their legal authority, or c) the agency had a duty to act but didn't.[8] And, since plaintiffs in environmental actions usually don't have access to all the data/evidence used by the agency, it is very difficult to show that an agency acted unreasonably.

Citizen Suits

Nor all environmental protection legislation allow for citizen suits. While (most) of the relevant federal legislation does, (most) states do not have similar provisions for violations of state-specific environmental laws.[9] So, even if there is a clear violation of an environmental protection law, citizens cannot sue to enforce the law, nor is the state obligated to enforce it.

When utilizing the citizen suit provision, plaintiffs are required to notify the relevant state agencies (usually the state environmental agency).[10] That agency is allowed to decline to pursue action against the alleged violator for any number of reasons (including that the agency is working with the violator on compliance and chooses not to pursue enforcement action, or that the alleged violations are 'unfounded').[11] It is then up to the plaintiff to continue without agency support, which increases their costs and difficulty of gathering enough evidence to prove a violation of the law.

It has also become it has become increasingly difficult for environmental plaintiffs to meet legal 'standing.' Standing essentially asks a would-be plaintiff, "what's it to you?" and demands that the answer meet certain requirements.[12] In extremely broad terms, the plaintiff has the burden to show that a) some kind of actual 'injury' or harm occurred; b) that the injury is fairly traceable to the conduct of the alleged violator; and c) that the court's decision can actually help fix or 'redress' the harm. In addition to these constitutional requirements, there has been an increase in recent decades of so-called 'prudential' requirements (i.e. discretionary judicial requirements). These requirements, when applied, require plaintiffs to show that they have somehow been affected by the violation in some individual and particular way, and that they fall into the 'zone of interest' that the legislation was intended to cover (e.g. a human rights group based in Alaska cannot sue to enforce protection of the endangered Floridian Orangina Toad). In recent years, courts have made it increasingly difficult for environmental litigation plaintiffs to satisfy the 'prudential' requirement.[13]

Public Nuisance & Toxic Tort Litigation[14]

Scientific evidence, methods, and data play critical roles in proving that x pollution caused y harm. And success or failure can depend on getting people to believe in the a) viability of the method/data collection process b) the conclusions drawn from data collected using that method, and c) the relevance of those conclusions to the larger issue. While courts have specific rules for introducing scientific evidence, the fact that judges and juries are not scientific experts themselves mean things often get extremely complicated and fuzzy in practice.

The baseline federal standard for admitting evidence is broad. All evidence is relevant, and theoretically admissible, if "(a) it has any tendency to make a fact more or less probable than it would be without the evidence; and (b) the fact is of consequence in determining the action."[15] However, it's difficult for non-experts to know whether scientific evidence/data is relevant or not, and courts require additional steps before scientific data is introduced.

Plaintiffs often hire expert witnesses who can testify to the importance and reliability of the data scientific (unfortunately, Rule 701 prohibits 'ordinary' or 'lay' witnesses from giving opinion testimony). However, the expert must also first show that he/she is an expert on the particular issue. They must also limit their opinions to a) testimony relevant to the case; b) opinions based on 'sufficient facts' or data; c) opinions based on 'reliable principles' and methods; and d) opinions where the expert has 'reliably applied' those principles to the facts. [11]

In practice, this widely used standard (called the "Daubert standard") puts new technology, unproven methods, and lower quality data at a significant disadvantage. Say, for example, two experts use similar raw data but apply different methods to come to different conclusions. In determining which conclusion to place more weight on, a judge might look to see which expert has more experience on the topic, or if one expert used conventionally accepted methods while another used a novel technique, or bases his/her conclusions on lower-quality data. In all these scenarios, the more 'traditional' expert and expertise will carry more weight.

EJ for All vs. Shady Business, Round 2

To place all of these legal challenges to community-sourced data in a (more depressingly realistic) context -- let's revisit the water pollution example from Part One. Here, we find that Shady Business, after being fined by the state environmental agency, has changed its tactics, and is now dumping its toxic waste directly onto its property. It has also contributed significant funds to a recent gubernatorial campaign, and, to the horror of many, the likely incumbent is indeed defeated by a 'pro-business' candidate, who hails Shady Business as an important driver of job growth.

Meanwhile, the toxic waste has slowly seeped into the groundwater, and local residents have seen a statistically significant increase in illnesses associated with certain toxins. So, the next generation of EJ For All has mobilized its base to force the company to stop polluting and pay for the harm it has done. Unfortunately, the new state legislature, under the direction of the new governor, signals to environmental agency staff the importance of informal and collegial compliance negotiations. After an unsuccessful attempt to influence proposed new regulations by participating in the agency decision-making process, EJ For All sues under the Clean Water Act citizen suit provision. Equally unfortunately however, the new administration has made it a priority to defund the environmental agency budget. Under this pressure, the agency decides not to pursue enforcement action.

Disappointed, yet undeterred, EJ For All presses on. Members of neighboring communities also come forward, with similar symptoms. A larger coalition forms, and it decides to bring a class action suit against Shady Business. In court, the coalition is eager to present the substantial amount of evidence it has collected, from water quality, to rises in local health problems and reductions in indicator species. It feels confident that a judge or jury will see the fairly obvious correlation between these and the dumping and the lack of enforcement. A local attorney steps forward, and offers to manage the case on a contingency basis.[16] There is a growing feeling of empowerment among the community coalition.

However, the lawsuit runs into several problems. Funds are low on the coalition's end; the opposition is well financed. Plaintiffs are intimidated; some lose their jobs at companies owned by Shady Business' parent company while others are offered money to drop out. The defense legal team raises objection after objection. They claim that the data collected does not follow established protocol, and bring several expert witnesses to testify as such. Finally, the judge, bound by the legal precedent established by the Supreme Court, weighs the evidence and determines that EJ For All's evidence insufficiently proves causation by the defendant, and the case is dismissed. Shady Business moves its operations to Mexico, and never has to pay damages. The community itself is devastated...but its youngest members are not defeated, and vow to fight on.

General Conclusions

It is one of life's most terrible truths that the facts of something can be warped and ignored using money or power, and that so often those with money and power choose to do so. But that is also why the growth of the community science movement is powerful: it makes community voices that much louder, and those with power a little less able to turn a blind eye.

While legal systems are critical for ensuring people abide by common rules and are duly punished if they violate them, these systems are almost always written by those in power, and rarely designed with the explicit intent to be accessed by everyone. In the United States, there are many legal mechanisms created with the intent to ensure environmental regulations are followed and violators punished for violating them. And yet, even with those goals, access to those tools is dependent on the agency, region, political pressures, and a host of structural and cruelly preventable limiting factors.

Still -- 'The Law' has never been a static force, immutable or frozen. It can move and grow and evolve to meet new needs and better redress old wrongs. Part Three of this series will focus on those areas of growth, as well as what we can do right now to hurry that evolution on: who knows how Hammurabi's Code might look like if he were born today?

[1]https://web.archive.org/web/20070909114038/http://www.wsu.edu/~dee/MESO/CODE.HTM

[2]http://mcadams.posc.mu.edu/txt/ah/Assyria/Hammurabi.html

[3]https://legiscan.com/WY/text/SF0012/id/1151882

[4] 6-3-414. (d)(ii) "Open land" means land outside the exterior boundaries of any incorporated city, town, subdivision approved pursuant to W.S. 18-5-308 or development approved pursuant to W.S. 18-5-403.

[5]http://www.wyofile.com/blog/lawsuit-challenges-constitutionality-of-data-trespass-laws/

[6]http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/florida-man-trade-gator-12-pack-beer-article-1.1551306

[7]https://wilsoncommonslab.org/2014/09/07/an-exploratory-study-on-barriers/

[8] The 'Article 78' process is an example of how the process works in New York State: www.nycourts.gov/courts/1jd/supctmanh/Self.../Special Proceeding2.pdf

[9] An example for how the process works in New York State can be found on the New York's Department of Environmental Conservation page here:http://www.dec.ny.gov/regulations/25226.html

[10] http://www.dec.ny.gov/regulations/25226.html

[11]http://www.dec.ny.gov/regulations/25226.html

[12] https://elr.info/sites/default/files/articles/23.10031.htm

[13] Lujan v. Defenders of the Environment is a Supreme Court case that established new, more difficult standards, and has had a significantly negative effect on environmental litigation.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lujan_v._Defenders_of_Wildlife

[14] One of the best (or worst, depending) examples of the difficulties plaintiffs face in pursuing corporate wrongdoing is covered in this story, which details the struggle of farmers in West Virginia to hold DuPont accountable for chemical pollution:http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/10/magazine/the-lawyer-who-became-duponts-worst-nightmare.html?_r=0

[15]https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_401

[16] Because of the difficulty of plaintiffs to have the resources to pay an attorney upfront, some attorneys take these cases on a contingency basis, meaning they get paid only if the plaintiffs win.

Follow related tags:

evidence legal litigation evidence-project

Citizen Science Investigations: aka ‘Common Legal Issues when using Community Sourced Data’

Image obtained at: http://www.thebluediamondgallery.com/wooden-tile/images/evidence.jpg

Lena Golze Desmond is an associate with Feller Law Group (www.feller.law) based in Brooklyn, which specializes in energy law. She is the lead collaborator of 'Law for the Environmental Grassroots,' (www.lawforenvgrassroots.com) an initiative focusing on expanding grassroots access to legal resources. She's a NYCELLI (New York City Environmental Law Leadership Institute) Board Member, an Environmental Leadership Program Senior Fellow, and managed to keep almost all of her houseplants alive this year!

This is part of Public Lab's 'Environmental Evidence' blog series - an examination of the ways in which the law and the legal system are helpful and harmful - for communities and advocacy groups seeking to use community-sourced data to activate change. 'The Law' can be an incredibly powerful tool for holding polluters accountable, but it is often overly complex, costly, and slow to respond to changing circumstances.

In this three-part blog, Part 1 will look at how the system currently works (and doesn't work). Part 2 will discuss common hurdles in using community-sourced data. Part 3 will focus on emerging trends, as well as ways in which community and advocacy groups can help shape the discussion of who gets to participate in the scientific process.

PART ONE: How it Should Work

Part 1 of this three-part series will give an overview of how citizen science and community- sourced data ("community data") should work in the legal realm, as well as issues that can negatively affect that process. It walks through the best-case scenario of using community sourced data to address a problem, from identifying the issue to using the legal system to redress it.

Step 1: Identifying the Problem

Maybe the movement starts with a bad smell and oil in the water. Reports of kids getting sick, or a decline in a certain species [1]. Perhaps it's part of an ongoing project, or even a positive trend: monitoring cases of asthma; documenting a return of life to a once-barren field; an increase in community gardens. Whatever the situation, the goal is to gather data to a) better understand what is going on and b) use that data to advocate for some action, whether it's cleaning up polluted areas or continuing a successful policy.

Step 2: Gathering the Evidence

Access to the tools to monitor and address threats to our environment and communities has generally been limited to 'professional' scientists or well-funded companies and research institutions. However, as groups (like Public Lab!) have been working to create easy-to-use and more affordable tools, we have seen an increase in the methods that are available to collect data and the types of private citizens engaged in data collection.

On one end of the spectrum is "citizen science" [2]. Citizen science often uses professional tools and equipment (loaned by professional scientists running the study), or involves basic observations that don't require equipment (e.g. bird counts), using studies designed by scientists. It may be well-funded, or include university and government agency partners. In the case of the water pollution identified in Step 1, a citizen science project might involve funding from a local university, and use metrics designed by a scientist.

On the other end is the emerging movement of "community science." With community science, data is usually collected by the public using low-cost means, such as low-cost (and low-quality) commercially available particulate matter sensors, or DIY tools, or basic photography. It is generally designed and conducted by community members [3]. For example: the local environmental justice coalition ("EJ for All") notices continuous dumping of what looks like hazardous waste in the river. One member obtains photographic evidence of the waste coming out of the pipeline located on the property of a manufacturing company (let's call it "Shady Business LLC"). The group then works with community volunteers to measure indicators of water quality (such as conductivity or turbidity) near the site of the discharge as well as downstream, upstream, and nearby tributaries to get a sense of the magnitude of the harm.

Regardless of the group and method, the goal is usually to gather the data so that a) conclusions can be drawn that b) are of a sufficiently high quality and c) use that data and those conclusions to be able to effectively address the issue.

Step 3: Turning Evidence into Action

After having gathered data, the next step is to use the data to prompt action. This 'action' can take many forms: publishing the data to a newspaper to raise awareness; submitting to a governmental agency or scientific institution; pressuring politicians to act. Another option is to use the legal system to force the polluter to stop what it's doing, or take steps to fix the problem.

Environmental litigation is very broad in scope. Each state has different rules, as does federal regulation, and it is difficult to neatly categorize them. That said, there are generally four types of legal action that are used to address environmental pollution (listed in order of prevalence):

- involvement in agency decision-making or petitioning for judicial review

- using 'citizen suit,' provisions in legislation (like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act) to bring a suit against the alleged violators [4]

- bringing public nuisance suit against someone engaged 'unreasonable' action [5]

- filing 'toxic torts' and civil lawsuits based on injury caused to someone from the pollution [6].

| Type of Action /Characteristics | Agency Decision-Making OR Petitioning for Judicial Review | Citizen Suits | Public Nuisance | Toxic Torts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How to Initiate | ADM: During Public Comment Notice period;PJR: Depends on the statute of limitations, but usually must file claim within appx 3 months | File Notice of Intent to Sue and serve on required parties | File lawsuit in civil court (usually state) | File lawsuit in court (state or federal) |

| Parties | Individual Commenters State/Federal Agencies | Plaintiff Alleged Polluter State Environmental Agency | Plaintiff Alleged Polluter | Plaintiffs (often Class Action) Alleged Polluter Insurance Companies |

| Legal Standards - Generally | Arbitrary & Capricious (i.e. there can be no reasonable explanation for action of agency) | Need to make sure that the law/legislation authorizes citizen suits (it is usually explicitly stated in the text) | A substantial and unreasonable interference with rights common to the general public | Federal Rules of Evidence |

| Legal Standards for Evidence | Agency must consider comments, but has discretion over how much weight to give them | Varies by state and by authorizing legislation; agency also has a certain amount of discretion in deciding whether of not to pursue action | The relevant state rules governing evidence | Federal Rules of Evidence401701702703 |

| Duration | During Comment Period: depends on agency, but usually 60 daysIf suing agency for its action: depends on specific state/federal statute of limitations. | Initial response (from state environmental agency): 10-30 daysIf agency decides not to assist and community continues on its own: 30 days -- 1 year | Less than 1 year | Years |

| Cost | During Comment Period: no cost -- low costIf suing agency for its action: cost of hiring attorney and filing motions | If agency decides to pursue: limited cost for individual plaintiffIf agency decides not to assist and community continues on its own: $1-15K | Main cost is usually cost of attorney and cost of presenting evidence | Some cases are on a contingency basis, but can go into millions |

Agency Decision-Making / Petitioning for Judicial Review

Participating in agency decision-making (e.g. writing or vocalizing a public comment) is often one of the easiest and most cost-effective entry points for individuals. The Environmental Protection Agency, as well as most state environmental agencies, are required to solicit public comment whenever considering action (or inaction) that might have an effect on the environment [7]. For example, when New York's Governor Cuomo was considering whether or not to allow fracking, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation received a record 200,000 public comments [8]. The Governor ultimately decided not to permit fracking in New York.

It is also possible to sue an agency or official for certain actions or inactions (petitioning for judicial review). While the rules are different in every state, an individual can challenge the decision of an agency to, for example, grant or deny a permit, amend rules, or issue a determination. However, the person(s) challenging the action generally have to show that the action was 'arbitrary and capricious,' meaning it did not follow logic and was made 'on a whim,' which is a pretty high bar to meet. Thus, if the agency/official can offer any reasonable explanation, the court will commonly defer to that explanation.

Citizen Suits

Some environmental legislation, notably the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, have so-called 'citizen suit' provisions, which allow private citizens to sue alleged violators of those laws. For example, the community group EJ For All decides to activate the 'citizen suit' provision of the Clean Water Act to stop Shady Business LLC from dumping waste into the river [9]. It provides the required notice of intent to sue to Shady Business as well as the state environmental agency. It also provides the agency with the photographs it took and water data it collected.

Public Nuisances

Public nuisance lawsuits are helpful for when there are no specific regulations prohibiting the conduct. In these suits, a judge can determine that the action is so unreasonable, the interference so substantial, and the relative 'utility' or worth of the conduct insufficient to merit the continuation of the action. However, for public nuisance suits, the plaintiffs have to show not only that the action is causing harm to the general public, but that they have suffered a unique harm. For example, if a factory spills toxic waste into a local public field -- that is harm to the general public, but only people who have been actually harmed -- their child became ill -- would have the 'standing' to sue. Public nuisance suits can be for money, but the goal is often to get the polluter/nuisance-maker to stop with the nuisance.

Toxic Torts

The final category -- toxic torts and similar litigation -- is the most expensive and time-consuming, which is why it is also, unsurprisingly, the least common. In these types of litigation, plaintiffs who have suffered harm because of the pollution sue the company responsible. Part 2 of this series will examine why these kinds of cases are especially unfriendly for community-sourced data.

In our case, the state environmental agency considers the evidence submitted by EJ For All, and determines the company did violate effluent limitations. It issues a penalty to Shady Business LLC. Hit where it hurts, the CEO Ronald Drumpf [10] orders the company to stop dumping in the river. The water quality returns to normal, kids are allowed to swim again, and all is well.

General Conclusions

That's how it's supposed to work. But community activists know all too well how often it doesn't happen that way. How often there's not enough time or money to do the research, to access the proper tools, to get people to listen, to afford attorneys, or how to influence the media, the government, the legal system. The next section gives an overview of obstacles that groups often face when trying to address an environmental issue in their community.

End Notes

- https://ccsinventory.wilsoncenter.org

- There is no one agreed-upon definition of 'citizen science.' Cornell's Orinthology Lab uses the working definition of projects in which volunteers partner with scientists to answer real-world questions. The White House, in its 2015 Memorandum on Citizen Science describes it as actions where "the public participates voluntarily in the scientific process, addressing real-world problems in ways that may include formulating research questions, conducting scientific experiments, collecting and analyzing data, interpreting results, making new discoveries, developing technologies and applications, and solving complex problems."

- Dosemagen, S, and G. Gehrke. 2016. "Civic Technology and Community Science: A New Model for Public Participation in Environmental Decisions." In Confronting the Challenges of Public Participation: Issues in Environmental, Planning and Health Decision-Making (Proceedings of the Iowa State University Summer Symposia on Science Communication). Edited by J. Goodwin. Ames, IA: Science Communication Project.

- https://www.law.umaryland.edu/about/features/feature0012/faq.html

- Rest 2d. Torts § 821B (1979).

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxic_tort

- https://www.epa.gov/nepa/how-citizens-can-comment-and-participate-national-environmental-policy-act-process

- http://www.ecowatch.com/new-yorkers-deliver-unprecedented-200k-comments-on-cuomos-fracking-rul-1881682190.html

- Under 33 U.S.C. 1365 of the Clean Water Act.

- No relation, of course.

Follow related tags:

evidence blog legal evidence-project

Interview: Chris Nidel on environmental evidence in court

A few months ago, as our first interview for the Environmental Evidence Project blog series (#evidence-project), we caught up with Chris Nidel, an attorney with Nidel Law, PLLC, based in the DC area. Lead image: satellite images of waste at a Maryland Perdue chicken farm from a case Chris fought in 2012.

_

_

As Chris writes in his bio, he's been involved in environmental law for a long time, starting shortly after getting a Master's in Chemical Engineering at MIT:

After graduate school, I went to work for a major pharmaceutical company doing drug process development. After a few years, I became disillusioned with the approach that the pharmaceutical industry, including the company I was working for, took toward putting profits over saving lives.

...

The combined realization that this company seemed more concerned about profits than creating cost-effective lifesaving medicines and that they seemed to care less about the illness and death that they were responsible for in their own right, forced me to leave. I went directly to law school at the University of Virginia. After graduating, I relocated to Dallas, Texas so I could work on major environmental and toxic tort litigation with the late Fred Baron at his firm Baron and Budd.

In the years since, Chris has worked at different firms and eventually started his own, and has been part of cases involving "cancer clusters, unsafe landfills, and air and groundwater contamination", and "air pollutants from TVA's coal fired power plants in Tennessee, Kentucky, and Alabama."

With all he's seen and done in environmental law, we wanted to ask some general questions about how evidence is used in court, from a pragmatic, real-world perspective.

I get this question all the time, where somebody says "how do I take samples that'll be admissible in court" -- and unfortunately, there's no right answer. ... I've had defendants in cases challenge EPA's own historical sampling. So you can have EPA scientists take samples and send them to whatever lab they feel is the appropriate lab to do the analysis, with whatever certification they have, and then the big company still comes back and say, "well, we don't believe those sample results. So while there is no silver bullet, the key is the reliability and ultimate credibility of the results. If the sampling and analytical methods are defensible...the data should be admissible"

Chris is realistic about the shortcomings of the current system, and emphasizes that you can never be 100% sure that evidence will be admitted, or that it will be effective:

Any time there's a legal argument in a court, there's always a chance that you'll lose it. If somebody said to me, "I want make sure I'm guaranteed that these samples -- or this evidence, or data -- is going to get admitted into court, I would be a fool to say, "sure, here's what you need to do guarantee it," because there's no guarantee. If you file a case against Monsanto, and the judge happens to play golf with the vice president of Monsanto, you may not be able to get those samples in. These issues may be out of your control and are independent of who did the analysis, and what qualifications they have, and what protocols they followed.

Data without advanced degrees

Chris has, however, worked on a case with Waterkeeper Alliance where samples were collected, stored, and managed by someone without a formal scientific degree. In this case, the person collecting samples was member of the local Riverkeeper organization and was an environmental advocate, but did not have extensive scientific training. Rather, she had a web-based certification for water sampling. According to Chris,

...the more important thing was that she actually followed a protocol. She got sterilized sample bottles from the lab, she wore sterilized gloves when she took the samples ... she filled out the chain of custody, she took it to the lab within the specified amount of time, she kept the cooler on ice, whatever was needed. And that was it. She took it to a lab, and they followed certified protocols. We didn't hire an engineer, or a chemist or a biologist to go out there and we didn't need to.

Due to this sampling protocol and detailed chain of custody, and since the laboratory followed an established analytical protocol, the samples were admitted as evidence in court without issue. In fact, the validity of the samples themselves wasn't even questioned in this case. Demonstrating the use of well-documented and rigorous methods can sometimes be sufficient for samples and data collected by non-accredited persons to be accepted as court-admissible evidence.

Clearly, there are nuances to this, and even without a cookie-cutter approach, there are pathways for people without a scientific degree to produce knowledge in ways that can be legally recognized. But that's what can be so frustrating about this topic -- it's not a clear set of rules you can just follow, and even if you follow what rules there are to the letter, you're still not guaranteed a result.

Expert witnesses

The example above specifically deals with samples that were analyzed later in a lab. What about other pathways? Many, it turns out, involve some kind of expert witness to authenticate, or essentially vouch for, the evidence. The judge or jury, who may not have relevant formal backgrounds to evaluate the evidence, won't be, as Chris puts it, "sitting there trying to speculate as to why they should believe one over the other" -- they'll rely on experts for that sort of thing. But who chooses the experts?

The problem with those experts are they are going to be paid by both sides. Clearly, they're going to have an opinion that's in your favor, and the other side is going to come in with an opinion in their favor, and... if you thought the DNC was bad, that's the sausage being made.

Not to mention -- what qualifies someone to be an expert in court? How much do expert witnesses tend to cost, and what happens if one side or the other can't afford an expert witness? We hope to circle back to this question in a later post.

_

_

Chris spoke at our June 6 OpenHour online panel on the topic of "Concepts of Proof" -- where he discussed his use of aerial photography in pollution cases. Watch the full video here.

Photographic evidence

Looking for a way through the thicket, we were really interested in photographic evidence, and how it might be different -- does it require expert authentication too? Chris said that it depends:

What conclusions or facts are you trying to establish? In our PCB case we used a lot of historic aerial photos... and EPA had an aerial photo lab assess the pictures -- here are barrels, etc, here are contours.

So interpretation by experts can enter into it. But what's most important is how it fits in with, and can relate to, other supporting evidence. One key aspect appears to be whether or not understanding a given piece of evidence is common knowledge, or if it requires certain training and experience to understand the implications of that evidence. Chris talked through a scenario we mentioned in #OpenHour about a photograph taken by a crane operator, who documented a plume of suspected pollution in a nearby waterway:

If you just put the guy in the crane on the stand, and you say, "You were up in the crane, you took these pictures. How did you take them? On what day? What were you looking at? Explain to us what direction you were facing when you took the pictures." [Because] the guy who sat in the crane who doesn't have any background, you probably don't get anywhere with it. You get the fact that there are pictures; you might even get them admitted. You might get the jury to be able to draw their own conclusions:

"I took the picture, I was on top of my crane, it's about 200 feet up, I was looking at the South Bay and this is what I saw."

The jury can look at that picture and they can understand that. Everything is good up to that point. Now, "I think this looks like a bunch of chromium was thrown into the bay. I'm just a crane operator, [but] my conclusion is that a bunch of chromium was going on in the bay that day."

That probably doesn't fly because neither the guy in the crane or the jury could conclude that it's necessarily chromium. On the other hand, if you can get that in front of the jury and the judge says, "I don't know that Johnny in the crane can tell us it's chromium, but I think it's admissible," and the jury could make their own deduction that there was chromium because you have other evidence. Let's say that you have evidence of what was in the barge from which the plume was coming. Now we have test data that shows that the barge was full of chromium, and now you have a photograph from Johnny in the crane that looks like a bunch of stuff is coming out of the barge, ergo, the jury decides chromium came from the barge.

You can also hire an expert and then the question would be does that expert have something that will help the jury themselves that the jury doesn't have without the expert? The expert comes in and says, "I've seen lots and lots of chromium discharges from power plants and I know what chromium looks like when it gets discharged, and this is clearly a chromium discharge." Then you get at it that way as well, and that's probably the typical way to do it, albeit the expensive way to do it. You hand off those pieces of evidence to someone else to draw the conclusion that you want to draw for the jury.

Given the complexity and uncertainty of the law as it plays out in court, we found it very helpful to hear about specific cases and examples. It seems that permissible and influential evidence is in the eye of, well, many beholders. While sometimes it may depend on internal, potentially invisible relationships between a judge and the case at hand, other times it's about walking a jury through enough solid testimony for them to draw conclusions about the value of the evidence themselves.

There are a few things we have learned to that can help us strengthen our cases as potential curators of evidence. We can make sure we're following existing protocol, as seen in the Riverkeeper example. We can also secure supporting evidence for our claim, such as seen in the crane operator example where supporting evidence could come from a lab or an expert witness.

Our hope is that in that the posts to come, more of these pathways to success, and limitations around evidence, are teased out. In the meantime, let's continue these discussions here and ping in with your questions and ideas. Thanks to Chris for making time to talk with us!

Questions

Questions we've addressed here:

- How is environmental evidence admitted into court-based legal processes?

- What can strengthen the case for evidence to be admitted in court?

- Who can vouch for, or interpret, evidence in court, and how is it weighed?

- Is photographic evidence treated differently from other environmental evidence in court?

- ...

Questions we'd like to address in upcoming posts:

- What collection, storage, and analysis protocols can strengthen environmental evidence in court?

We're moving these questions into the new Questions system -- so feel free to repost one here:

| Title | Author | Updated | Likes | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How do you merge GPS logger data into photographs? | @warren | over 7 years ago | 1 | 11 |

| Who can vouch for, or interpret, evidence in court, and how is it weighed? | @warren | about 8 years ago | 1 | 0 |

| What are the limits to what can be interpreted from a photograph without an expert witness? | @warren | about 8 years ago | 0 | 0 |

| What are ways to strengthen photographic evidence in court? | @warren | about 8 years ago | 1 | 0 |

| What's the best way to archive/store a timelapse video? | @warren | over 8 years ago | 1 | 3 |

Follow related tags:

evidence blog legal openhour

Enforcing Stormwater Permits with Google Street View along the Mystic River

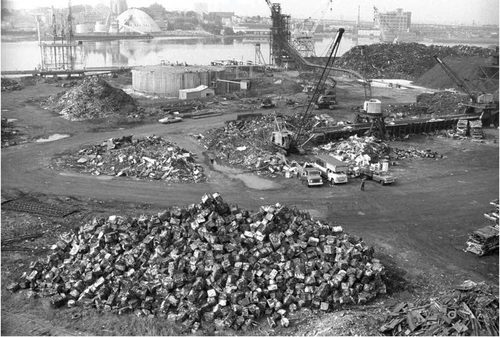

Compressed autos at Mystic River scrap yard, Everett, Massachusetts, 1974. Spencer Grant/Getty Images. CC-NC-SA

In 2015 the New America Foundation asked @Shannon and me to write a chapter for their Drone Primer on the politics of mapping and surveillance. I worked in an example of positive citizen surveillance by the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) that I’d heard about in a session at the 2015 Public Interest Environmental Law Conference. I’ve excerpted and adapted my writeup of the CLF case as a part of our ongoing Evidence Project series. If you know of similar cases please get in touch!

Geo-tagged aerial and street-level imagery on the web can be a boon to both environmental lawyers and the small teams of regulators tasked by US states with enforcing the Clean Water Act. Flyovers and street patrols through industrial and residential districts can be conducted rapidly and virtually, looking for clues to where the runoff in rivers is coming from. Combining aerial and street-level photographs with searchable public permitting data, the 1972 Clean Water act’s stormwater regulations are now more enforceable in practice than they have ever been (Alsentzer et. al., 2015).

State and federal environmental agencies often do not have time or resources to adequately enforce permits under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) that regulates construction and industrial stormwater runoff, and roughly half of facilities violate their stormwater permits every year (Russell and Duhigg, 2009). Enforcement can be picked up by third parties, however, because NPDES permits are public. Plaintiff groups and legal teams conduct third-party enforcement through warnings and lawsuit filings. Legal settlements from lawsuits recoup the plaintiffs legal costs, and can also include fines whose funds are directed towards community-controlled Supplemental Environmental Projects that help improve environmental conditions in the violator’s watershed. The Conservation Law Foundation (CLF), a Boston-base policy and legal non-profit, operates in precisely this manner, recouping their costs through lawsuits and directing funds to Supplemental Environmental Projects in the Mystic River Watershed.

In 2010 a neighborhood group approached the CLF about a scrap metal facility on the Mystic River. Observable runoff demonstrated the facility had never built a stormwater system, and a quick US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) NPDES permit search revealed that they had never applied for or received a permit. The facility was flying under the EPA’s enforcement radar, and so were four of the facility’s neighbors.

Between 2010 and 2015 CLF’s environmental lawyers initiated 45 noncompliance cases by looking for industrial facilities along waterfronts in Google Street View, and then searching the EPA’s stormwater permit database for the facility’s address. Most complaints are resolved through negotiated settlement agreements, where the facility owner or operator funds Supplemental Environmental Projects for river restoration, public education, and water quality monitoring that can catch other water quality criminals. Together, CLF and a coalition of partners such as the Mystic River Watershed Association, are creating a steady stream of revenue for restoration, education, and engagement in the environmental health of one of America’s earliest industrial waterways.

Regardless of their effect, legal threats are stressful, often expensive, and can take years to resolve. Even when threatened polluters are acting in good faith to clean up their systems, the process of identifying and persuading companies to comply with environmental regulations can be strain relationships in communities. Non-compliant small businesses on the Mystic River that have been in operation since before the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972 may never have been alerted to their obligations under the law. Their absence from the EPA database reflects mutual ignorance from bureaucrats of businesses and businesses of bureaucracy. However, businesses bear the direct costs of installed equipment, staff time, and facility downtime, indirect costs of professional reputation from delayed operations or identification as a polluter, and transactional costs of paying for legal assistance or court fees. Indirect and transactional costs are hidden punishments that can accrue regardless of guilt or readiness to comply.

To combat the negative perceptions that can accrue from the use of legal threats, CLF proactively works to fit itself into a community-centered watershed management strategy. CLF and their partners run public education and outreach campaigns and start with issuing warnings that aren’t court-filed (Alsentzer et. al., 2015). Identifying and working with businesses operating in good faith is a tenet of community-based restoration efforts. By using courts as a last resort and participating in public processes where citizens can express the complexity of their landscape relationships, CLF and their partners are increasing participation in environmental decision-making and establishing the legitimacy of restoration and enforcement decisions.

Regulations and permit databases can often be tough to put to work, but the CLF’s case was fairly straightforward: They simply searched for company’s addresses in a publicly available database. We would love to hear cases of more groups using this approach or other simple modes of regulatory engagement.

Excerpted and Adapted from Mathew Lippincott with Shannon Dosemagen, The Political Geography of Aerial Imaging, 19-27 Drones and Aerial Observation, New America Foundation 2015.

Sources and Further Reading:

Alsentzer, Guy, Zak Griefen, and Jack Tuholske. 2015. CWA Permitting & Impaired Waterways. Panel session at the Public Interest Environmental Law Conference, University of Oregon.

Conservation Law Foundation Newsletter “Coming Clean”, Winter 2014;

D.C. Denison, “Conservation Law Foundation suing alleged polluters”, Boston Globe, May 10, 2012.

Russell, Karl and Charles Duhigg, Clean Water Act Violations are Neglected at a Cost of Suffering. In The New York Times, Sept 12, 2009. Part of the Toxic Waters Series

Follow related tags:

evidence epa blog water

The many types of evidence

As a followup to our introductory post, Gretchen and I wanted to explore the many different types of evidence, and talk about their differences, even before getting into the legal definitions and ramifications. Whether you're taking a photo, reading data from a sensor, or cataloging health symptoms, we'd also like to ask what types of information you're interested in using as evidence, and we'll do our best to follow up on each type over the course of the series.

(Lead image by @Matej on Newtown Creek)

Evidence could mean something used in a legal case, like Scott Eustis's work in photographing coal contamination by United Bulk in the Mississippi. It could mean creating a map to establish land tenure claims, as Maria Lamadrid has worked on in Uganda. Or it could mean analyzing microscopic pictures of dust to quantify particulate pollution.

We want to cast a wide net here, so for starters, we're looking at a number of broad categories of potential evidence:

- physical samples of air, water, or soil

- digital sensor readings of many types

- photographic, audio or video records

- timelapse, infrared photos, thermal or microscopic photos

- photo metadata, such as timestamps or GPS data

- colored strips of paper or indicator tubes, like litmus tests

- also, photographs of such colorimetric indicators

- spreadsheet data resulting from an analysis of, for example, images or sensor data (we have a specific case in mind for this)

- human sensory data collection -- like odor logs or direct visual monitoring

- health symptoms in animals

- human health symptoms

This is a huge topic, and the more we dig in, the more diverse understandings of the term we encounter. In discussions with some of our interviewees for this series, we've encountered distinctions between screening and analytical samples, and samples used in enforcement processes or to gauge remedial progress. We'll look into these to learn more, and get back to you. Can you suggest other types?

Note that the item above, about spreadsheet data, is especially interesting to us -- that is, what about lab analyses themselves? Does a report about a sample or a measurement constitute evidence? Some of the above examples (like this one) are drawn directly from projects we're engaged in, and we'd love to hear from others about specific real-world cases involving different types of evidence.

For one, we're interested in how microscopic photographs of air pollutants like silica (above image by @mathew), and the associated datasheets from their analysis, can be properly collected, stored, and presented as evidence. How does maintaining a chain of custody work with digital data? Do equations in a spreadsheet need to be preserved and documented along with the data themselves? How is that best done -- do we need to, for example, keep a log of timestamps and authors for each edit?

One thing we came across in our exploration has to do with the use of spreadsheets in court, and was hard to believe! Cogent Legal runs a pretty interesting blog on preparing evidence (and derivative graphics) for court, and discussed the logistical and procedural challenges to using or even adding to a spreadsheet used in evidence:

One of Cogent Legal's clients recently went to trial with a spreadsheet similar to the one used for this post. The spreadsheet printed out to be 28 pages long, and the original column had no total on it. For a printed exhibit at trial, counsel added a total to the spreadsheet, but opposing counsel objected to its admission, arguing that the spreadsheet had been altered and lacked foundation. Thus, the attorney offering the spreadsheet as evidence displayed the electronic spreadsheet for the jury on a courtroom screen, and then led the witness through the process of summing the column's total in Excel. Once this total was established, the opposing counsel stipulated to admission of the original document (and also stipulated to the admission of many similar documents). -- http://cogentlegal.com/blog/2014/06/excel-for-litigators/

We'll be looking to compile some best practices to -- hopefully -- avoid that kind of painful walkthrough.

Another usage we're exploring is #timelapse photography (above timelapse by @tonyc) -- useful in monitoring all kinds of activity over long periods of time. There are EPA recognized techniques (like Method 82) which employ timelapse photography of smoke plumes. Folks at LEAFFEST 2016 will be trying out some timelapse methods, and we'll want to know how this sort of evidence ought to be handled as well.

In any case, we'll surely be updating this post as we discover more, and we appreciate any additions you can offer! Thanks, and stay tuned.

Follow related tags:

evidence timelapse legal with:gretchengehrke