A version of this story by Nadya Peek is published in Public Lab's Community Science Forum, Issue 16.

In 2012, I was conducting a literature review of sensitivity and selectivity in olfaction–in machine olfaction and animal olfaction. Although the review itself was rather dry, some of the (humorous) detours that didn’t make it in the review are documented here.

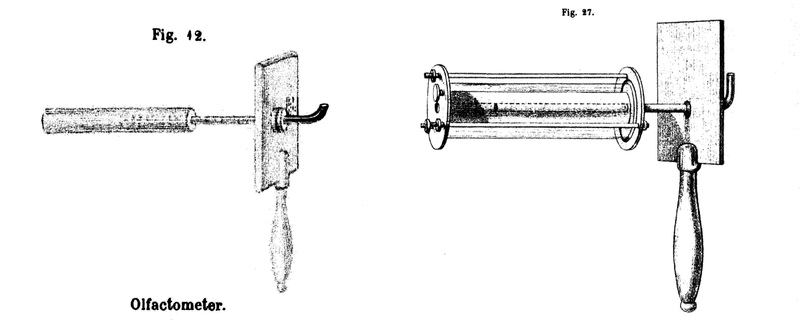

Zwaardemaker’s olfactometers, or Riechmesser. The second is an improvement upon the first, with an interchangable odorant chamber. From Physiologie des Geruchs.

Zwaardemaker’s olfactometers, or Riechmesser. The second is an improvement upon the first, with an interchangable odorant chamber. From Physiologie des Geruchs.

In 1762, Rousseau wrote in Émile, or On Education, that smell was “the sense of the imagination, as it gives tone to the nerves it must have great effect on the brain.” Little did Rousseau know that the olfactory nerve was the only cranial nerve besides the optic nerve that does not route through the brainstem. He continues, “Smells by themselves are weak sensations. They move the imagination more than the sense and affect us not so much by fulfillment as by expectation.” Smell as a cue to a memory may draw whimsical or visceral responses. An extremely sensitive reflex may result from these memories, at least in rats; apparently they can smell down to 0.04 parts per trillion of 2,4,5-trimethylthiazoline, which happens to be an odorant exuded from the anal glands of cats and red foxes (Laska et al. 2005).

A setup for measuring time taken to detect a smell. Not sure where the big pointy thing goes to… From Physiologie des Geruchs.

A setup for measuring time taken to detect a smell. Not sure where the big pointy thing goes to… From Physiologie des Geruchs.

Analytical instrumentation pales in comparison, only managing to detect odorants at parts per billion levels at best (with ideal sample presentation, slow analysis, and no masking odorants present).

Even now, smell experiments (e.g. for determining permissible odour levels around landfills) are often conducted with panels of experts instead of with instrumentation alone. In fact, some legislation around smell is based on number of complaints reported, because detecting the smell levels directly is deemed too complicated and expensive. TSA dogs are sniffing your bags for bombs or apples. But to be able to measure things like how long it takes to detect the smell or where the smell is stronger, people have been inventing funny machines at least since the early 19th century.

In 1895, Henrik Zwaardemaker, a professor at Utrecht University, published Physiologie des Geruchs, a treatise on olfaction and odorants. In it, he details different methods of presenting odorants to subjects in a controlled fashion.

Image courtesy of Nasal Ranger

Image courtesy of Nasal Ranger

But the funniest man-chine is preserved for the present day! Might I share the NASAL RANGER™. Look at how SCIENTIFIC these people look! The Nasal Ranger™ does nothing more than provide some ratio of active carbon filtered and non-filtered air. So you can smell just the air, or smell nothing, or something in between. You can decide if there is a big difference between filtered and not-filtered air. It’s not that fancy. Yet it evokes TECHNONOSE, or a BETTER-THAN-YOURS nose. Here they even describe it as a “mobile artificial nose,” even though the nose part actually belongs to the person holding the retro-futuristic contraption.

Another silly instrument, another day. Next thing you know, they’ll be measuring odorant levels in degrees Brix.

Nadya Peek develops unconventional digital fabrication tools, small scale automation, networked controls, and advanced manufacturing systems. Spanning electronics, firmware, software, and mechanics, her research focuses on harnessing the precision of machines for the creativity of individuals. Nadya directs the Machine Agency at the University of Washington where she is an assistant professor in Human-Centered Design and Engineering.

1 Comments

@warren has marked @nadya as a co-author.

Reply to this comment...

Log in to comment

Login to comment.